|

Can Convicted Offenders Be Classed as 'Volunteering' for Therapy? Working with Men who Have Committed Sexual Offences and Volunteered for Treatment in a Prison-based Therapeutic Community1

Patrick Mandikate, Geraldine Akerman

HMP Grendon, University of Birmingham

[Sexual Offender Treatment, Volume 7 (2012), Issue 2]

Abstract

Men 'volunteer' to transfer to HMP Grendon to address their offending behaviour in a prison-based therapeutic community. This work includes them discussing their sexual interests and offending and possibly having to modify their sexual interest to fit with society's norms. They may think that if they are to reduce their risk, and be released from prison, they have to go through this process, so can this be described as coercive? Other men choose to change their views of children, women and other potential victim groups and so could be deemed to have 'volunteered' for therapy. This paper will describe the work undertaken at HMP Grendon with men who have committed sexual and violent offences and some of the ethical implications and difficulties working in this setting and with this client group.

Key words: Sexual Offenders, Treatment, Volunteering

Treatment as rehabilitation

Therapeutic communities

The development and ethos of therapeutic communities (TCs) has been described extensively elsewhere (Akerman, 2002; Genders & Player, 1995; Shine, 2000; Shine & Morris, 1999), and more recently by Ware, Frost and Hoy (2009) and Sullivan and Shuker (2010), so this will not be repeated in detail here. However, in brief the therapeutic community model was developed when men returning from conflicts and war zones were awaiting treatment for what we would now recognise as post traumatic stress reactions. It was noted that while they were waiting in doctors' waiting rooms they spoke to each other and recognised the similarities in feelings. They then felt that they were not alone or abnormal and could seek support from each other to manage symptoms and problems- that society can be the agent of change. The principles underpinning TCs in custodial settings are those of democratisation (learning from mistakes, decision making, and living with consequences of these); tolerance (i.e. allowing problematic behaviour to emerge so it can be examined and challenged); communalism, (acknowledging that basic emotions and instincts are common and learning how others manage these) and reality confrontation (observed behaviour is challenged and pro - social behaviour practised).

HMP Grendon

HMP Grendon is a category 'B' (medium secure) prison, which also houses category 'C' prisoners (lower secure) and comprises of six Therapeutic Communities (including the assessment unit) housing 200 plus adult men who were described as more damaged, disturbed and dangerous than the average inmate by Shine and Newton (2000). Shine and Newton found that service users in their sample scored a mean score of 24 when assessed using the Psychopathy Checklist Revised (Hare, 1991). The comparable sample of high-security prisoners at that time had a mean score of 22. Birtchnell and Shine (2000) found a high percentage of personality disturbance (86% assessed as having at least 1 personality disorder, the mean number per service-user was 4.02), and significant levels of emotional distress, e.g., anxiety, depression, and histories of abuse (Shine & Newton, 2000). Following treatment service users have shown a reduction in anti-social behaviour, reoffending, and increased psychological well-being, (Newberry, 2011; Newton, 2010; RSG, unpublished) and ability to discuss and understand offending behaviour (Akerman, 2010).

A TC within a prison provides an environment where a range of behaviours (including those exhibited in the build up to their offending) can become apparent and therefore open to assessment and change. It provides an opportunity to practice and refine skills learned on other offending behaviour programmes in a meaningful way.

Residents live together on a wing of 40-45 adult men and their fantasies, thoughts, feelings and behaviour are discussed in the thrice - weekly small therapy groups, the twice - weekly community meetings, and all other places where residents spend their time. One of the communities houses service-users who have committed offences with a sexual motivation or whose behaviour within prison leads to some concern in this area. However, the residents are still free to mix with residents from other wings throughout the day, for instance at the gymnasium, exercise, chapel, or for education. There is no segregation by offence type and so men who have committed sexual offences are integrated and work alongside men who have committed other offences (murder, robbery, arson and so forth) and no segregation cells, so any breaches of order are managed by the community.

|

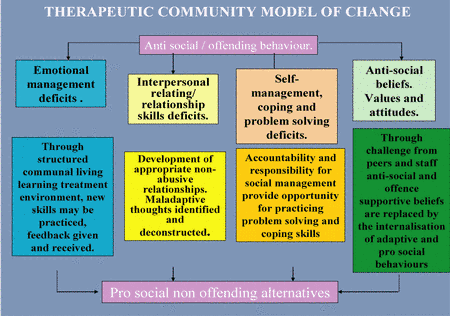

| Figure 1: Therapeutic community model of change |

The model of change is described as social therapy, which integrates social learning, and psychodynamic principles. It is accredited by the Correctional Services Advice and Accreditation Panel (CSAAP)2, a body which monitors the quality of offending behaviour programmes and by The Community of Therapeutic Communities, which is part of the Royal College of Psychiatrists' Centre for Quality Improvement3. Psychotherapy takes place to help to develop understanding of the effects of formative experiences, which have lead to anti-social views.

The model integrates exploration of motivation, fantasy, attitudes, and relationships within a psychodynamic formulation. Behaviour is observed and explored as it happens and maladaptive beliefs are identified and challenged. The environment enables opportunities for all aspects of functioning to be exposed, those that lead to offending and developing the ability to take responsibility in terms of taking care of the place you live in, for instance watering plants, cleaning, washing and so forth.

Ethical implications of a TC

It is understood that treatment should be holistic involving human rights, ethical practice and improved well-being (Birgden & Cucolo, 2011, Ward & Stewart, 2003). However, there some ethical dilemmas, such as: - Is it ethical to monitor/observe behaviour in custody?

This is a requirement in assessing behavioural change. For example the British Psychological Society (BPS, 2006) code of ethics states that you should seek consent from client prior to intervention, so is observation an intervention? Haag (2006) states that risk assessment is for society so is not the same as a psychotherapeutic intervention and Bonner and Vandecreek (2006) make the point that when client is failed so is the public, and staff at HMP Grendon are both treatment providers and members of the public. - As a therapist who is the client?

In terms of risk assessment the employer is the National Offender Management System, (NOMS) whose mission statement promises: 'To help them lead a law abiding life following release'. Therefore the aim of treatment is less conflict with their community and no re-offending following effective treatment. Generally in therapy the client is the person in treatment. The 'slipperiness' of these concepts raises their own difficulties for the therapist particularly, as they relate to an ethical framework which may be more complex than in the treatment of other offenders. There may often be an element of coercion in therapeutic work, the spoken or unspoken suggestion that work has to be done before release. There are specific expectations regarding confidentiality, risk and public protection and indeed the work may be defined as done in the interest of the 'public' instead of, or as well as, the patient/ offender/resident (Jones, 2012). The men who transfer to HMP Grendon do so by applying and stating what they want to achieve. However, they may well not understand fully what is expected of them and the possible negative effects of being in therapy. For instance increased levels of distress, an increased level of risk if they do not complete, and while they are undertaking the work, raised emotions. Within a TC longstanding members (known as culture carriers) will help newer members through difficult times. In the past they may well have left impulsively, leaving relationships, families and employment in their wake. - Changing sexual preferences

Participation on the programme encourages those with deviant sexual interests and preferences to change these, which they may not want to do, but fear that they have to do in order to be released. Furthermore, is it even possible to change sexual preferences? (See Marshall, O'Brien & Marshall, 2009 for further details).

Integrated programme

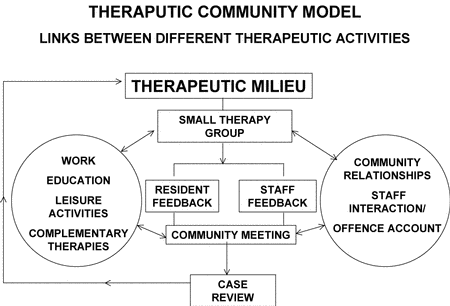

All aspects of the community are integrated into work for the residents, how they engage in therapy groups, in education, at work, with staff and so forth, and all is open for discussion and scrutiny.

Figure 2 shows how all aspects of the work are fed through therapy groups, compared to previous behaviour and work towards eventual release.

|

| Figure 2 |

The work also entails looking for examples of the compulsion to repeat maladaptive/ previous patterns of behaviour and where a relationship or situation in the TC resembles an earlier problematic one. The individual will react in the same way as he/she did before providing the whole community with tangible evidence of the problem, which is then open to scrutiny, analysis and change. Where this relates to offending behaviour it is called offence paralleling. This is discussed further (Akerman 2010, 2011, 2012, Akerman & Beech, in press, Dowdswell, Akerman & Lawrence, 2010) and is challenged routinely and more pro social skills developed.

The TC looks at each individual in a holistic manner and encourages the development of a rounded fulfilling lifestyle in line with the Ward and Gannon (2006) Good Lives model. We recognise that residents have similar goals and aspirations as non-offenders, but the way they have gone about achieving them has caused them problems. They are encouraged to develop all aspects of their functioning.

The therapeutic relationship

The importance of the therapeutic relationship between therapist and client is paramount in determining how effective the treatment will be. Recent research focuses on different aspects of this dynamic, for instance Marshall and Serran, (2004) and Marshall, Marshall, Serran and Fernandez's (2006) work on therapists' style and Frost's (2004) research on engagement in treatment, emphasise the importance of the relationship, indicating that therapy at Grendon needs to attend to such issues. Ackerman and Hilsenroth (2003) discuss a range of studies looking at therapist styles. They found that the therapist should demonstrate that they are working together with the client, and that the therapeutic alliance was developed and enhanced through referring to common ground, for instance, being able to disclose similar incidents from your own life experience. The application of the concept of the therapeutic alliance in this sense is limited as therapeutic alliance also relies on the therapeutic agent behaving contrary to the 'disturbed' model that the client brings into treatment whilst validating that the client is doing the best they can given their limited emotional resources at that time. The alliance is further challenged when working with service-users who have committed sexual offences as the therapist may find it difficult to refer to common ground when it comes to understanding deviant sexual fantasy and arousal and their origins in the client's past.

In order to work effectively with those who have committed sexual offences, therapists need to be able to tolerate hearing details of violent and sexual offences against others. Lewis (1997, p. 211) spoke of the need to provide a 'corrective emotional experience ', as distinct from the 'defective emotional experience' that existed in the early years of rejection and inconsistency of care. Consistency, continuity and a caring environment provide the context for 'the personal journey to personality reformation'. Pearlman and Saakvitne (1995) describe how clients in therapy unconsciously invoke re - enactments of previous relationships, making the relationship between the therapist and client potentially healing or threatening, which presents a considerably complex environment in which the therapists' skills are having boundaries constantly tested. All staff at HMP Grendon are involved in the treatment, including prison officers. It is vital that there is a supportive therapeutic relationship.

Nitsun (2006, P.13) suggests that 'group psychotherapy has marginalized sexuality and desire in the evolution of theory' and yet this is the focus of work. Nitsun draws on his experience of many years working with clients in psychotherapy and finds that they feel unable to discuss sexuality. Many of the service -users at Grendon have committed serious transgressions of sexual boundaries; it would seem likely that they would find it even more difficult to discuss their sexuality and sexual behaviour, given the feelings of shame and guilt this evokes. Davies (1998) describes how therapists use themselves in an affirming therapeutic relationship to help the client form a template for future relationships. The therapeutic culture within Grendon provides the reparative role so that the resident can develop more appropriate relationships. The facilitators tread a fine line between being authority figures, holding parental roles and establishing a therapeutic alliance where residents feel safe to disclose deviant attitudes. As stated above, discussing sexual issues is not easy to do; discussing sexual offending can prove even more difficult.

Much of the power of a sexual fantasy stems from its secrecy and so to expose it to public scrutiny can make the resident feel very vulnerable. The relationship with staff can be particularly difficult for men who have spent long periods of time in higher security prisons, often preceded by other institutions such as children' s homes. These experiences can result in residents testing boundaries as a means of finding out where those boundaries are in order to feel safe, because staff in similar positions of power have abused them in the past.

It is worth noting that the prison officers at Grendon do a highly specialised job and whilst most will have received some training in TC concepts and treatment methods, few will have undertaken any professional training. Whilst most clinical staff are experienced practitioners who have completed specialist training, most prison officers gain their training by facilitating groups alongside a more experienced facilitator until they feel sufficiently confident to do so alone. Adjusting to, and dealing with, the tensions inherent in this role becomes part of the clinical discussion within the TC, and structures such as staff post - group ' feedbacks ' and weekly staff support, or 'sensitivity ' meetings, form essential components of the treatment process. In these meetings, staff are able to discuss the impact that the toxic content of therapy has on them, so that they do not project any feelings evoked onto residents (or other members of staff) when working with them throughout the day. Members of staff must also ensure that splits do not develop amongst the different disciplines.

Fantasy modification programme

When aspects of offending, such as sexual preoccupation, or deviant sexual or violent fantasies, (which may have previously been used to cope with difficulties), get in the way of therapy residents can undertake more specialised work to learn behavioural techniques. A range of fantasy modification techniques is taught, including Directed Masturbation, described by Marshall (2006) as pairing arousal with appropriate images with masturbation thus reinforcing their excitement. Other techniques taught are: Covert Sensitisation (Marshall & Eccles 1996), a technique that pairs personally aversive consequences (such as being in prison, creating more victims, or being publicly humiliated) with each step of an offence-related fantasy; and Satiation, associating offence-related fantasies with boredom. There is discussion about what goods (in terms of Ward & Stewart 2003) are achieved through fantasy, e.g. physical satisfaction (health), intimacy (intimacy), emotion regulation (inner peace), and how else they could be achieved. Each participant identifies what they have gained from fantasy and how these needs could be met in pro-social ways. There is recognition that it is easier to manage this arousal in the context of a prison than in the real world and plans were made to revisit this work with offender managers as they prepare for release. The role of sexual preoccupation and using sex as a coping strategy is discussed and alternative strategies devised. The principal of urge surfing or distress tolerance (that is remaining in a state of arousal without reinforcing it through masturbation, with the knowledge that the urge will pass in a few minutes), and the use of thought stoppers as a means of managing arousal are also discussed and practised. The programme is described more fully by Akerman (2008).

Research

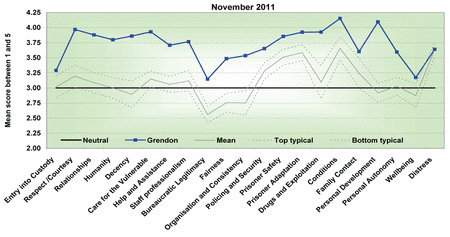

In a TC model there is a lot of emphasis placed on involvement and autonomy given to service-users/therapists. They are involved throughout process in the research undertaken, comment from point of application to administration. Examples of research include; assessing risk reduction (Newton, 2010; Shuker, 2010), relationships between staff and service-users (Niven, Holman & Totterdell, 2010), developing measure of current sexual interest (Akerman, Bishopp & Beech submitted), and the Measure of Quality of Prison Life survey, (Liebling, 2012, Walsh, Barnes, & Lee, 2011), which is monitored by the Audit and Corporate Assurance group at NOMS. The measure of quality of prison life is a major survey, which seeks responses from residents in every prison in England and Wales and asks their view of how they are treated in custody. HMP Grendon's scores have consistently fallen above the top of the typical range.

Figure 3 Shows how the residents rated the quality of their life in prison on the dimensions noted.

|

| Figure 3 |

A score close to three indicates neutral perceptions on average, notably above three indicates positive perceptions on average, and below three indicates negative perceptions.

Summary

In summary, the TC model is complex and all encompassing. It can open up all sorts of wounds which the resident may well not expect when they apply to undertake the work, but ultimately is aimed at changing lives for the better. It is a programme which requires tenacity and resilience to remain in treatment when powerful emotions are evoked, rather than leave, or use drugs, alcohol or sex to ameliorate emotions, and a dedicated and well supported staff team to maintain the boundaries required for such work to take place. There are a number of ethical issues raised by undertaking therapy with men who have committed sexual offences and for whom their freedom relies on the outcome of the work, as discussed above.

Notes

1 This paper was presented at the 12th Conference of the International Association for the Treatment of Sexual Offenders (IATSO) September 5-8th, 2012 Charité University Berlin, Germany

2 The Correctional Services Advice and Accreditation Panel is a non-statutory body that helps the Ministry of Justice to develop and implement high quality offender programmes. Its main work is to accredit programmes for offenders.

3 The Community of Therapeutic Communities is a standards-based quality improvement network for national and international therapeutic communities.

References- Ackerman, S.J. & Hilsenroth, M.J. (2003). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting on the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review, 23, 1-33.

- Akerman, G. (2002). Development of a checklist to measure community minded behaviour in a prison - based therapeutic community Forensic Update, 69, 17-29.

- Akerman, G. (2008). The Development of a fantasy modification programme for a prison-based therapeutic community. International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 29, 180-188.

- Akerman G. (2010). Undertaking therapy at HMP Grendon with men who have committed sexual offences. In E. Sullivan and R. Shuker (Eds.), Grendon and the emergence of forensic therapeutic communities: Developments in research and practice (pp. 171-182). UK: Wiley.

- Akerman, G. Bishopp, D. & Beech, A.R. (submitted). The Development of a Psychometric Measure of Current Sexual Interest. Psychology, Crime and Law.

- Akerman G. & Beech, A.R. (submitted). Exploring Offence Paralleling Behaviours in Incarcerated Offenders. Prisons and Prison Systems: Practices, Types and Challenges. USA: Nova Publishers.

- Birgden, A. & Cucolo, H. (2011). The treatment of sex offenders: Evidence, ethics and human rights. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 23, 295-313.

- Birtchnell, J. & Shine, J. (2000). Personality disorders and the interpersonal octagon. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73, 433-448.

- Bonner, R. L. & Vandecreek, L.D. (2006). Ethical decision making for correctional mental health providers. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 33, 542-64.

- British Psychological Society (2006). Code of ethics and conduct. Leicester: British Psychological Society.

- Daffern, M., Jones, L. & Shine, J. (Eds.). Offence paralleling behaviour: A case formulation approach to offender assessment and intervention. Chichester: Wiley.

- Davies, J.M. (1998). Thoughts on the nature of desires: the ambiguous, the transitional and the poetic. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 8, 805-23.

- Dowdswell, H., Akerman, G. & 'Lawrence' (2010). Unlocking offence paralleling behaviour in a custodial setting-A personal perspective from members of staff and a resident in a forensic therapeutic community. In M. Daffern, L. Jones and J. Shine (Eds.), Offence paralleling behaviour (pp. 231-243). UK: Wiley.

- Frost, A. (2004). Therapeutic engagement styles in child sex offenders in a group treatment programme: A grounded theory study. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and treatment, 16, 191-208.

- Genders, E. & Player, E. (1995). Grendon: A study of a therapeutic prison. Clarendon Press.

- Glaser, W. (2003). Therapeutic Jurisprudence: an ethical paradigm for Therapists in Sex Offender Treatment Programs. Western Criminology Review, 4, 143-154.

- Haag, A. (2006). Ethical dilemmas faced by correctional psychologists in Canada. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 33, 93-109.

- Hare, R. D. (2003). Manual for the Revised Psychopathy Checklist, 2nd Ed. Toronto, ON: Multi-Health Systems.

- Jones, D. (2012). Therapy in Perversity: Seduction, Destruction and Keeping Balance. In A. Aiyegbusi, G. Kelly (Eds.), And G. Adshead (Series Editor). Professional and Therapeutic Boundaries in Forensic Mental Health Practice (Forensic Focus) (pp. 53-62). UK: Jessica Kingsley.

- Lewis, P. (1997). Context for change (Whilst consigned and Confined): A challenge for systematic thinking. In E. Cullen, L. Jones & R. Woodward, Therapeutic Communities for Offenders (pp.71-89). Chichester: Wiley.

- Liebling, A. (2012). What is 'MQPL'? Solving puzzles about the prison. Prison Service Journal, 202, 3-5.

- Marshall, W.L. (2006). Approaches to modifying sexual interests. NOTA16th Annual conference University of York 20-22nd September.

- Marshall, W. L. & Eccles, A. (1996). Cognitive behavioural treatment of sex offenders. In A Sourcebook of Psychological Treatment Manuals for Adult Disorders by Van Hasselt, V.B & Hersen, M. New York: Plenum Press.

- Marshall, W.L., O'Brien, M.D. & Marshall, L.E. (2009). Modifying sexual preferences. In A.R. Beech, L. A. Craig and K.D. Browne (Eds.), Assessment and treatment of sex offenders. A handbook (pp. 311-327). Chichester: Wiley.

- Marshall, W.L. & Serran, G.A. (2004). The role of the therapist in offender treatment. Psychology, Crime and Law, 10, 309-320.

- Marshall, W.L., Marshall, L.E., Serran, G.A. & Fernandez, Y.M. (2006). Treating Sexual Offenders: An Integrated Approach. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group UK.

- Newton, M. (2010). Changes in prison offending among residents of a prison-based therapeutic community. In E. Sullivan and R. Shuker (Eds.), Grendon and the emergence of forensic therapeutic communities: Developments in research and practice (pp. 281-292). UK: Wiley.

- Nitsun, M. (2006). The group as an Object of Desire. Exploring sexuality in group therapy. London, New York: Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

- Niven, K., Holman, D. & Totterdell, P. (2010). Emotional influence and empathy in a therapeutic prison: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. In E. Sullivan and R. Shuker (Eds.), Grendon and the emergence of forensic therapeutic communities: Developments in research and practice (pp. 233-246). Chichester UK: Wiley.

- Pearlman, L. A. and Saakvitne, K. W. (1995) Trauma and the therapist: Counter-transference and vicarious traumatisation in psychotherapy with incest survivors. London: W.W. Norton and Co. Ltd.

- Rehabilitation Services Group (Unpublished). Do democratic therapeutic communities reduce offending? Rehabilitation Services Groups. NOMS. December 2010.

- Shine, J. (Ed.) (2000). HMP Grendon: A compilation of Grendon research. PES HMP Leyhill.

- Shine, J. & Morris, M. (2000) Addressing criminogenic needs in a prison therapeutic community. Therapeutic Communities, 21, 197-218.

- Shine, J. & Morris, M. (1999). Regulating Anarchy: The Grendon programme. England: Springhill Press.

- Shuker, R. (2010). Personality disorder: Using therapeutic communities in an integrative approach to address risk. In E. Sullivan and R. Shuker (Eds.), Grendon and the emergence of forensic therapeutic communities: Developments in research and practice (pp. 115-136). Chichester UK: Wiley.

- Sullivan, E. & Shuker, R. (Eds.). Grendon and the emergence of forensic therapeutic communities: Developments in research and practice. Chichester UK: Wiley.

- Walsh, L., Barnes, A. & Lee, P. (2011). Measure of Quality of Prison Life. Ministry of Justice/National Offender Management Service.

- Ward, T. & Gannon, T. (2006), Rehabilitation, etiology, and self-regulation. The good lives model of rehabilitation for sexual offenders. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 11, 77-94.

- Ward, T. & Stewart, C.A. (2003). Criminogenic needs and human needs: A theoretical model. Psychology Crime and Law, 9, 125-143.

- Ware, J., Frost, A. & Hoy, A. (2009). A review of the use of therapeutic communities with sexual offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54 721-742.

Author address

Geraldine Akerman

Grendon Underwood, Aylesbury

Bucks, HP18OTL

England

Geraldine.akerman01@hmps.gsi.gov.uk

|