|

Treatment of Comorbid Mental Disorder and Sexual Offending: A Critical Analysis

Yvette A. Kelly1 & Susan Hatters Friedman2

1Mason Clinic Regional Forensic Psychiatry Services, Waitemata District Health Board

2University of Auckland and Case Western Reserve University

[Sexual Offender Treatment, Volume 14 (2019), Issue 2]

Abstract

Aim/Background: Elevated rates of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depression) are found among sexual offenders. However, information about effective treatment to prevent recidivism among these mentally disordered sex offenders is sparse.

Methods: Therefore, a critical analysis of extant literature was completed.

Results: Studies often conflated serious mental illness with intellectually disability, personality disorders, and substance use disorders, making findings difficult to interpret.

Conclusion: The literature indicates that when treating mentally disordered sexual offenders, the symptoms of mental illness should first be controlled, and comorbid substance use disorders treated. Treatment in a group setting using a CBT-based model was most commonly reported, with only some individual therapy described. Staff support to prevent burnout is also recommended.

Keywords: sexual offending, schizophrenia, psychosis, mental illness, treatment

Introduction

Definitions

There has been no consistent definition made of a group who constitutes those with a serious mental illness that have committed a sex offence. Clearly "Mental Disorder" is a broad term, as is "Serious Mental Illness". A clear definition of this review's subject group, those who have committed a sexual offence but also suffer from a major mental disorder, was considered pertinent for results regarding their treatment to be generalizable.

A range of disorders were specifically considered for inclusion or exclusion in the review definition. The Mental Health diagnoses targeted were those that may hinder participation in standard Sex Offender Treatment Programs (SOTP) through their effects on thought, organisation, and concentration due to their association or potential association with psychotic symptoms. Schizophrenia is a diagnosis fitting this description, and was therefore a target diagnosis of the review. However, it must be noted that debate exists in the literature about the origins of Schizophrenia and whether this is a single condition (Bentall, 1993). Therefore individuals with identical diagnoses may have quite different psychopathology and even a narrow definition of mental disorder that includes those with a schizophrenia diagnosis likely leads to a heterogeneous group.

Diagnoses hindering participation in standard SOTP due to effects on cognition specifically were not the targets of this review. Therefore Intellectual Disability (ID) or specific dementias were not targeted.

Personality disorder has been defined by the American Psychiatric association as a class of mental disorders characterized by enduring maladaptive patterns of behaviour, cognition, and inner experience, exhibited across many contexts and deviating markedly from those accepted by the individual's culture. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). By definition, Antisocial Personality Disorder is expected to be common amongst offenders and prison populations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which is supported by research findings (Booth & Gulati, 2014; Dunsieth et al., 2004).

Similarly substance misuse and addiction disorders have been identified as common amongst sexual offenders (Kraanen & Emmelkamp, 2011). Paraphilia, defined as the experience of intense sexual arousal to atypical stimuli (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), when associated with sexual deviance is also expected to be common amongst those who have committed sexual offences (Mann, Hanson, & Thornton, 2010).

Hence, we have assumed standard treatment programs for sex offenders would accommodate the diagnoses of antisocial personality disorder, substance use disorder, and paraphilia, and potentially even partially treat these. These disorders have therefore been excluded from the definition of "Mental Disorder" used for the purpose of this review. However, these disorders are identified as co-morbidities that may be present amongst Mentally Disordered Sex Offenders (MDSO) some of which there may be specific treatment for.

The definition of a "sex offender" must also be considered. Sex offenders may be considered a heterogeneous group on their own (Lambie & Seymour, 2006; Sakdalan & Gupta, 2014; Lambie & Seymour, 2006; Yates, 2003). Even those convicted of identical sex offences, by their legal definition, may have very different intentions or motivations. Sex offending as a behaviour crosses socioeconomic, educational, racial, and religious groups (Saleh & Guidry, 2003) possibly further adding to heterogeneity of the MDSO group. Legal definitions of sex offences are problematic, where different jurisdictions will categorise sex offences differently. Using a legal definition of sex offender may also exclude those with sexually problematic behaviours not having led to charges or convictions, where some MDSO may be diverted to the forensic psychiatric system due to their major mental illness (Hughes & Hebb, 2005; Moulden & Marshall, 2017).

Thus for the purpose of this review, Mentally Disordered Sex Offenders will be defined as those who have: - Committed a sexual offence, from the less serious offences of frotterism or voyeurism through to the most serious offences of rape and child sex offences. This type of offending therefore constitutes those meeting legal definitions of committing a sex offence though is intended to include individuals that have not necessarily attracted a conviction.

- Been diagnosed with a serious mental illness that has the potential to cause psychotic symptoms. This includes the diagnoses of Schizophrenia, Schizoaffective disorder, Bipolar Disorder, and Major Depressive Disorder.

- Despite exclusions, these criteria still lead to a highly heterogeneous group, due to the multiple different crimes combined with the multiple different diagnoses discussed.

Relationship between Mental Disorder and Sexual Offending

Exact rates of severe mental illness in sex offenders is unknown (Booth & Gulati, 2014). However, there is evidence of increased rates of Mood (Booth & Gulati, 2014; Dunsieth, et al., 2004) and Psychotic disorders (Booth & Gulati, 2014). Particularly telling is the research conducted by Fazel and colleagues (2007) which involved the analysis of Swedish National Register data collected for more than 8,000 sexual offenders between 1988 and 2000. This indicated that male sexual offenders were significantly more likely to have a severe mental illness than the general population of close to 20,000 controls. Sexual offenders were 4.8 times as likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, 3.4 times as likely to be diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and 5.2 times as likely to be diagnosed with other psychotic disorders when compared to members of the general population (Fazel, Sjostedt, Langstrom, & Grann, 2007).

There is conflicting evidence around the impact of mental illness on sex offending. There is evidence that mental disorder increases recidivism in sex offenders (Langstrom, Sjostedt, & Grann, 2004) as well as evidence of no difference in risk (Bonta, Law, & Hanson, 1998; Phillips et al., 2005). A review performed by Mann, Hanson, and Thornton identified major mental illness, other than depression, as having a small effect on the recidivism of sex offenders. However, this relationship was not maintained when the large Langstrom study cited above was removed as an outlier (Mann, Hanson, & Thornton, 2010).

Regardless of the relationship, it is difficult to determine how the motivations of MDSO to sexually offend relate to their specific mental illnesses (Smith, 2000). Some MDSO may be sex offenders that happen to have a mental illness, whereas others' offending may be closely associated with symptoms of mental illness such as command hallucinations or disorganised behaviour. One must also address the possibility of sex offending leading to a mental disorder rather than the converse. Mood Disorders are prevalent in sex offenders and may be subsequent to a range of confounders such as imprisonment, loss of employment or relationships (Booth & Gulati, 2014).

This area is also worthy of research as there is evidence that sex offences committed by psychiatric patients are more serious, such as rape and child sex offences (Harris, Fisher, Veysey, Ragusa, & Lurigio, 2010). Therefore prevention of reoffending for MDSO may be more pertinent compared with non-disordered sex offenders to prevent more severe outcomes for victims.

Sex Offender Treatment Programs

Most modern Sex Offender Treatment Programs (SOTP) are based upon Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) (Garrett, 2015; Schaffer, Jeglic, Moster, & Wnuk, 2010; Yates, 2003). Targets of treatment include attitudes supporting sexual offending, anger management, victim empathy, deviant sexual arousal, and relapse prevention (Yates, 2003). This may include assessment of pornography use and its role in sexual aggression (Kingston, Malamuth, Fedoroff, & Marshall, 2009). CBT has also been demonstrated as an effective way of treating a range of behaviours in mentally disordered individuals (Perkins, 2010).

The Risk-Needs-Responsivity (RNR) Model is a well-established model for offender assessment and rehabilitation to guide treatment programs, including the use of CBT (Willis, Yates, Gannon, & Ward, 2012). This model has demonstrated effectiveness in those that have committed sexual offences, and assesses the offender's level of risk, targeting treatment at specific offenders' criminogenic needs using individualised interventions (Bonta & Andrews, 2007). The Good Lives Model is considered complementary to the RNR model by guiding use of treatment with a strengths-based approach and has also inspired delivery of sex offender treatment programs (Willis et al., 2012).

There has been some discussion in the literature regarding whether Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) may be more beneficial than CBT in the treatment of sex offenders due to it assisting offenders in regulating affects and with impulse control. DBT based treatment may also allow for benefits of group and individual therapy given its delivery through both of these means (Sakdalan & Gupta, 2014).

Group therapy has been recognised as being beneficial for those with problematic behaviours generally where group members benefit from identification of problems and being challenged by their peers (Mela & Ahmed, 2014). However different offenders may require vastly different treatments, such that group therapy alone is insufficient and individualised treatment is beneficial to determine and address specific areas (Yates, 2003). Individualised treatment may also be required in cases where offenders decline group therapy (Garrett, 2015).

As well as psychological treatments, there is evidence that pharmacological treatments, such as anti-androgen therapy, are useful for treatment of sex offending behaviours (Assumpcao, Garcia, Garcia, Bradford, & Thibaut, 2014; Bradford & Pawlak, 1993). A further area for biological intervention may be treatment of physical illness where there may be evidence that such illness could be associated with sex offending, such as an association found with thyroid disorders (Langevin, Langevin, Curnoe, & Bain, 2009). Though optimising physical health alongside mental health is a likely goal of all health professionals, this may also be beneficial in decreasing risk either directly or indirectly. Good treatment of co-morbidities, such as substance use, may also prevent sex offender recidivism (Hartwell, 2004).

Hence it is apparent that a range of treatments exist that may be used to prevent recidivism in sexual offenders. Therefore, the goal of this review was to determine the efficacy of various treatments for sexual offenders diagnosed with a major mental illness.

Method

Five databases were searched to identify research into treatment of MDSO. These included: PubMed, Medline, Cochrane Library, PsychINFO, Clinical Key, and the Psychology and Behavioural Sciences Collection.

Search terms used were selected based upon definitions described above, and were searched for their presence in the abstract of the papers. There was careful consideration of search terms due to a suspicion that many articles would discuss whether sex offending behaviour is a mental disorder. However it was difficult to determine search terms sufficiently comprehensive to capture literature about MDSO treatment without including multiple articles discussing sex offending as a mental illness. Child molester or paedophilia were considered as search terms, though appeared to lead to extensive literature concerning these sexual interests and crimes as a mental disorder in themselves so were not included as search terms. We resigned to manually exclude many articles referring to the offending as a mental disorder. Wildcards were not used in the search. The search terms selected were therefore combinations of: - Sex Offender

- Rapist

- Treatment

- Rehabilitation

- Mental Illness

- Mental Disorder

- Psychosis

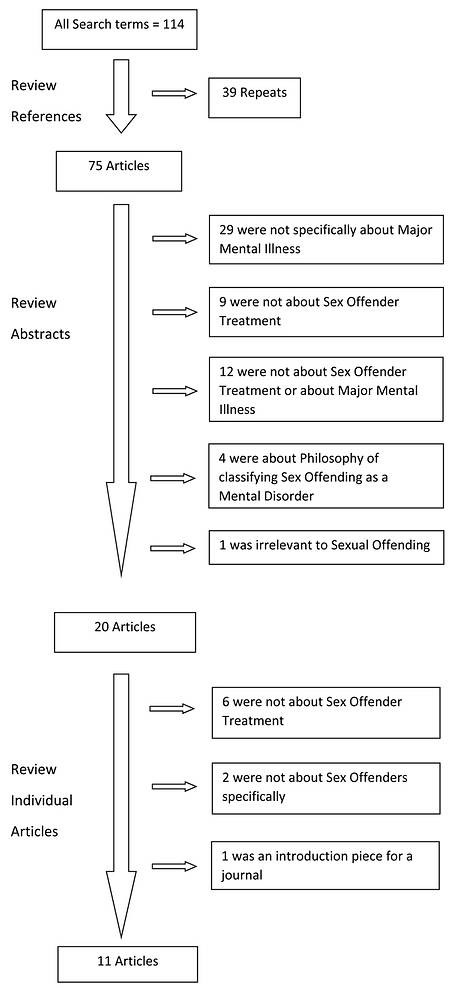

Please refer to Table 1 for specific search term combinations and the number of results from each database. This method identified 114 articles, of which 39 were repeats. Abstracts of the remaining 75 articles were reviewed. Abstract review excluded a further 55 articles leaving 20 papers for full review. Inclusion for full article review was left broad to ensure all possible appropriate articles would be captured. This was decided due to the question posed having had apparently little attention in research. Please refer to Figure 1 for a summary of the exclusion of articles.

Table 1: Search Term Combinations |

| |

Cochrane |

Medline |

PubMed |

PsychINFO |

Psychology &

Behavioural

Sciences

|

Clinical

Key |

TOTAL

FROM

SEARCH

COMBINATION |

| Sex Offender + Treatment + Mental Illness |

0 |

6 |

6 |

20 |

10 |

0 |

42 |

| Sex Offender + Treatment + Psychosis |

0 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

| Sex Offender + Treatment + Mental Disorder |

0 |

5 |

4 |

11 |

3 |

0 |

23 |

| Sex Offender + Rehabilitation + Mental Illness |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

5 |

| Sex Offender + Rehabilitation + Psychosis |

0 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

| Sex Offender + Rehabilitation + Mental Disorder |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

1 |

0 |

4 |

| Rapist + Treatment + Mental Illness |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

8 |

| Rapist + Treatment + Psychosis |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

| Rapist + Treatment + Mental Disorder |

1 |

0 |

0 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

16 |

| Rapist + Rehabilitation + Mental Illness |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| Rapist + Rehabilitation + Psychosis |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| Rapist + Rehabilitation + Mental Disorder |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

| TOTAL FROM EACH DATABASE |

1 |

14 |

15 |

63 |

20 |

0 |

114 |

|

| Figure 1 |

Results

As predicted, papers regarding sex offending being a mental illness itself accounted for the bulk of the studies requiring exclusion due to a lack of relevance. Only one article identified in the database searches was excluded due to being entirely irrelevant to both the subject of sexual offending and of major mental disorders. This irrelevant article was about nomenclature used to describe mental health professionals. This was identified in the search due to their humorous use of the phrase "Psycho the rapist" (Walter, 1991).

On review of the full papers, a further nine articles were excluded due to a lack of relevance, most because they did not apply to treatment specifically. Studies with any element of treatment were included, as a paucity of research meant these may provide guidance for future research into MDSO treatment. The number of articles sufficiently relevant for review was eleven. The method of exclusion is illustrated in Figure 1. Throughout these eleven papers there were changeable inclusion criteria for the MDSO group. Some studies included individuals with cognitive deficits or intellectual disability alongside those with major mental illness. Others included personality or substance use disorders. This made results of these studies difficult to analyse alongside one another as the groups studied were not comparable.

These eleven papers also included few studies of sufficient strength to allow clear conclusions to be made. Two were dissertations and one a chapter from a book. None of these articles had therefore been peer reviewed, effecting the strength of this evidence. Two articles were case studies, with one being the chapter described above. Limitations of case studies are well known, with only one participant where the placebo effect cannot be measured. The measures were also made by those delivering treatment, with associated biases. However these studies were examined for the review to identify possible research areas for further refining using stronger study designs.

There were only two studies researching outcomes of treatment of a moderately sized group of MDSO, most specifically addressing the review question. However, these studies included mental disorders not intended to be examined by this review such as intellectual disability. These both had the same primary researcher, and some of the same study participants. They also both had selection biases where participants opted for treatment, leading to a self-selection bias, or were given treatment according to when they were hospitalised. Despite these limitations, different mental disorders had been analysed and some findings about MDSO could be identified (Stinson, Becker, & McVay, 2015; Stinson, McVay, & Becker, 2016).

A further two papers were not original research, but were discussion pieces about treatment of MDSO. There were also three studies not specifically about treatment of MDSO but included or separated treatment of MDSO from a study design looking at alternative study questions such as risk of recidivism or assessment of MDSO. All eleven articles were recent, with the earliest published in 2004. This may indicate a new interest in this area after realisation that MDSO may require different treatment from other sex offenders.

Prior to examining the findings, evidence available already appeared insufficient for a definitive answer to the review question. However, examination of these papers was considered valuable to clarify areas for further research or whether further research was required. All research papers had male participants, though there was mention of female sex offenders in the discussion papers.

Summary and Analysis of Identified Papers

Due to the paucity of research in the area of the review question, every paper will be discussed in turn.

The first was a pilot study of a SOTP called the Safe Offender Strategies (SOS). This was a manualised group-based SOTP emphasising self-regulation development over ten modules. SOS was devised for the treatment of sex offenders with mental disorder or cognitive impairment. It included didactic learning about specific areas of dysregulation, and participants completed homework recording their individual difficulties associated with on-going problem behaviours (Stinson et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2016). This study included 156 forensic psychiatric inpatients who had committed a sexual offence or exhibited behaviours meeting criteria for a sexual offence. This group had a wide range of psychiatric difficulties including diagnoses not the focus of this review, such as autistic spectrum disorders (Stinson et al., 2015).

The efficacy of SOS was examined using the Sex Offender Treatment Intervention and Progress Scale (SOTIPS) and its predecessor inventories. This tool was noted to have been well-established in correctional sex offender populations, but not in MDSO. Measures were completed every six months, up to two years post-treatment. Results indicated that the more groups that MDSO attended, the significantly less non-contact sexual aggression by those individuals. Though there was evidence for improvement in contact sexual aggression this did not reach significance for the entire follow up period of two years. It was noted many of the pilot study participants had not completed the entire group at the time of data analysis, yet had demonstrated significant changes in their behaviour, thoughts, and self-regulatory and self-management abilities. This may be relevant to the treatment being useful at early stages, but may also indicate the value of group members' motivation and commitment to treatment. It was also noted that those not participating in this voluntary treatment had more prominent psychotic symptoms (Stinson et al., 2015). This may indicate that good control of psychotic symptoms may allow better treatment engagement, and that this is a priority for initial treatment.

The same researchers conducted a study comparing SOS with Relapse Prevention (RP) treatment in 91 patients within a secure psychiatric setting. RP treatment differed from SOS as it emphasised avoidance of triggers rather than learning skills to manage triggers. RP was considered the SOTP Treatment As Usual for those without major mental disorder. Again this group included individuals with mental disorders not the focus of this review such as intellectual disability. This may have affected results where the SOS group had more cognitively impaired participants than the RP group. Additionally, the SOS group had fewer participants who suffered from a psychotic disorder than did the RP group. Results demonstrated a significant difference between treatment groups. SOS patients had less post-treatment arrests and hospitalisation with a follow-up period of up to three years. There was also an overall trend of the SOS group being housed in less restrictive environments on release. This included fewer returns to higher levels of security and supervision levels decreasing over time, such as requiring less psychiatric rehospitalisation (Stinson et al., 2016). The decreased need for psychiatric rehospitalisation may have been associated with the SOS group having less participants suffering from a psychotic disorder rather than this being a more effective treatment for this group.

The primary author also conducted a study using the same participants as the pilot study examining risk factors in MDSO leading to non-completion of the SOS program (Stinson et al., 2016). Those least likely to complete the program suffered from psychosis, intellectual impairment, or borderline personality disorder. Those with more arrests, longer admission, and recent physical aggression were also less likely to complete treatment. It concluded by reporting that treatment providers should monitor psychiatric symptoms severity in order to minimise non-completion of treatment. This study did not examine treatment of MDSO per se, but identified relevant factors for completion of treatment.

A further two papers each discussed a case study (Clark, Tyler, Gannon, & Michael, 2014; Garrett, 2015). One was a case of bipolar disorder where his most serious offence was indecent assault (Garrett, 2015). This individualised treatment focussed on formulation, then used a CBT approach emphasising relapse-prevention. The treatment focussed on specific behaviours such as problematic eye contact and use of pornography. There were educational aspects to this treatment, such as the participant no longer making intense eye contact after being informed this was intimidating rather than indicating confidence. The treatment also included mental health relapse prevention techniques, such as knowledge of early warning signs. Limitations of this study included insufficient information about the therapy to enable replication, and results being subjective due to the participant refusing psychometric inventories. Clinicians believed he improved in engagement, insight, and eye contact; and assessed him as being lower risk sufficient to allow planning for discharge from the medium secure facility.

The second case study used Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) to treat offence related trauma (Clark et al., 2014). This was used on the premise that MDSO experience more re-traumatisation from SOTP than other sex offenders, negatively affecting their ability to benefit from conventional SOTP. As EMDR was beneficial in treating Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) after fewer treatments than CBT, the goal was to clarify whether EMDR was effective in treating offence-related trauma in a MDSO. The participant was diagnosed with schizophrenia, had two recent convictions for gross indecency, and a history of other sexual offending. He had completed two conventional CBT SOTP, having not contributed in his first SOTP but made some gains in the second. Discharge attempts failed due to his apparent sabotage and he disclosed PTSD symptoms associated with offending.

This led to a hypothesis that his sabotage was subsequent to offence-related trauma (Clark et al., 2014). He was assessed with Impact of Events Scale-Revised (IES-R) and was in the moderate range for post-trauma psychopathology. The Subjective Units of Distress and Validity of Cognitions inventories were used to measure progress. The participant received EMDR by the standard protocol. During treatment it was discovered he had experienced significant trauma associated with a prison assault, which was also treated by EMDR. Results indicated a decrease in trauma and the participant himself reported relief (Clark et al., 2014). This case study focussed on offence-related trauma resolution rather than decreased risk of sexual offending. However, treatment of offence-related trauma may allow better engagement in SOTP and prevention of sabotage as per this case.

The remainder of the articles included discussion papers, and assessment or recidivism studies.

One of these recidivism articles examined 401 MDSO who had completed the Clearwater Program, a CBT based RP program operational since 1981 at the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Canada, with a follow up period of up to 27 years (Kingston, Olver, Harris, Wong, & Bradford, 2015). High risk sex offenders completing this program have been demonstrated to be significantly less likely to reoffend than untreated sex offenders, though lower risk offenders do not demonstrate a significant difference in sexual reoffending following treatment (Gordon, 2015). The study analysed recidivism according to diagnosis, all having completed the Clearwater Program. The group most representing MDSO were described as Non-Substance related Mental Disorders (NSMD) and consisted of 34 individuals who predominantly suffered from mood or psychotic disorders. Two studies were reported in this article, examining inpatient and outpatient treatment. Both studies found those with NSMD were less likely to reoffend than those with other diagnoses, such as substance use or personality disorders, after having completed the program (Kingston et al., 2015).

A study of MDSO Assessment included individualised assessment of how the MDSO's illness relates to their offending. They suggested assessing whether problem behaviours pre-dated the illness, mental state at the time of the behaviours, nature of the behaviour when in different mental states, and co-morbidities such as substance use. This group also noted assessment should be made over a lifetime of offences, rather than assessing few recent offences. The predominant interest in this study was the validity of structured professional judgement tools in MDSO, which were found to be valid overall but problematic when assessing dynamic risk factors (Kelley & Thornton, 2015).

The remaining papers were discussions regarding alternative treatments for MDSO. Hughes and Hebb (2005) included formal sex education amongst suggestions for treating MDSO. They noted that MDSO had deficits in their knowledge of sexual health and relationship skills, possibly secondary to having been excluded from learning these skills via a peer group as per a normal developmental process. The patient education provided on sexual health and relationships skills was considered useful for patients other than those that had exhibited sexual aggression, such as the sexually vulnerable. The sexually aggressive and the sexually vulnerable may not be mutually exclusive groups. These two areas of education were provided in separate modules to allow tailoring of education according to patient need (Hughes & Hebb, 2005).

This discussion paper (Hughes & Hebb, 2005) also mentioned staff education and training. It was noted that staff can find patients exhibiting inappropriate sexual behaviour particularly challenging, and require specific training about managing this population to prevent burnout. There were also observations that there is often inadequate recording of inappropriate sexual behaviours in clinical files, where a behaviour type is reported but not described. Staff training around recording of inappropriate sexual behaviour may be required to ensure appropriate information is communicated for risk assessment, preventing both the over and under-estimation of risk.

A discussion by Harris and colleagues (2010) focussed on policy regarding MDSO. They identified a number of stabilising factors preventing recidivism, such as stable housing and employment. Difficulties in securing these needs for MDSO were emphasised. A need for treatment of the mental illness was also emphasised. This was said to be necessary to optimise SOTP engagement and to treat other factors contributing to offending, such as command hallucinations. They also identified staff training as necessary for treatment and recidivism prevention, suggesting a need for specialised case managers. Harris and colleagues also questioned the role of public policies on MDSO recovery, such as sex offender registers (Harris et al., 2010).

Harris and colleagues (2010) theorised that MDSO could be grouped into those posing risks similar to non-MDSO, and those behaving inappropriately secondary to mental illness. They reported that less serious sex offences in sex offenders without a major mental illness may be associated with a ‘slippery slope' into more serious offending. However this may not apply in MDSO as these less serious offences may be secondary to disinhibition or social inappropriateness compared with the majority of sex offenders with other high risk variables such as paraphilia. They suggested that these different offenders may be treated in different settings. MDSO were acknowledged as having difficulty complying with court-ordered conditions, often due to disorganisation, though lenience in conditions was not suggested (Harris et al., 2010).

Boles (2012) completed a dissertation about the training of those working with sex offenders. This training totalled seven hours and aimed to assist those working with MDSO to assess and treat these individuals. The dissertation goes into the detail of the training program formulated, which was based upon the Good Lives Model and the Mentally Ill/Problematic Sexual Behaviour Program. However, no evaluation of the efficacy of the program was reported.

Another dissertation examined treatment completion in MDSO (Ashbeck, 2015). It was found pre-treatment Global Assessment of Function (GAF) scores were more predictive of treatment non-completion than mental disorder. However, it was also noted that those with mental disorder had lower GAF scores than offenders without mental disorder.

Conclusions

Due to a paucity of research regarding the treatment of problematic sexual behaviours in MDSO, few true conclusions can be made about best treatment. However, there are many areas for further exploration.

Treatments in the literature reviewed tended to be based on a CBT model (Garrett, 2015; Kingston et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2016). Avoiding triggers for offending appeared to be a valuable aspect to treatment as per the successes resulting from RP models, such as the Clearwater Program (Kingston et al., 2015). However, SOS treatment empowering MDSO to manage their behaviour when encountering triggers may decrease risk further (Stinson et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2016). Despite the Risk-Needs-Responsivity (Bonta & Andrews, 2007) model addressing these behaviours, this model did not emerge in the search. This may be due to not having been examined in MDSO specifically and may be worthy of research in this group. Major mental illness may be considered as a responsivity factor where tailored treatment accommodating the symptoms and treatment of major mental illness may lead to greater treatment success (Mitchell, Wormith, & Tafrate, 2016).

Most treatment appeared to be applied in a group setting (Kingston et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2015; Stinson et al., 2016), with some individualised treatment (Clark et al., 2014; Garrett, 2015). Should individualised treatment be available, this may allow more specific therapy targeting particular behaviours, such as inappropriate eye contact (Garrett, 2015). As MDSO are heterogeneous, therapy may be best delivered after these individuals are grouped together with others that have similar deficits and needs (Harris et al., 2010). This may be difficult in smaller or dispersed populations. Additionally, some offenders may require education of appropriate behaviours. Relationship and boundary education may be areas included in psychosexual education for effective treatment of MDSO (Hughes & Hebb, 2005).

Regardless of the treatment programs selected, assessment of progress is believed to be required to determine treatment effect. GAF may be a helpful way of frequently assessing progress (Ashbeck, 2015), alongside more extensive risk inventories at less frequent intervals (Kelley & Thornton, 2015). Appropriate staff training was also emphasised regardless of the treatment method to ensure appropriate abilities in identifying and reporting behaviours assisting with risk assessment and progress, as well as to prevent burnout in a confronting area of work (Harris et al., 2010; Hughes & Hebb, 2005).

Alongside discussion of the structures for MDSO treatment programs, it has been surmised that co-morbid symptoms or conditions require treatment prior to entering such a program. The most important and likely intuitive treatment required is optimal treatment of the mental disorder itself. This is both to minimise the disorders effects on treatment engagement (Stinson et al., 2016) as well as other factors of the mental disorder that may put the individual at risk of sexually offending, such as command hallucinations (Harris et al., 2010).

Another co-morbidity where treatment may optimise engagement in a SOTP includes offence-related trauma. Assessing offence-related trauma may require a separate therapy program, and EMDR may possibly be the treatment of choice for such an affliction (Clark et al., 2014).

It appears that clear definitions of the MDSO group are required to further research or findings in this area. The changing definitions affected the ability to compare these groups in this review. Some of the diagnoses that were grouped with those with the major mental disorders of interest in this review included ID, personality disorders, and substance use disorders.

We propose that sexual offenders with a major mental illness be defined separately from other diagnoses with high prevalence amongst sexual offenders. This is despite MDSO possibly having significant co-morbidities of these other conditions. Clear definitions of MDSO would allow the possibility of combining research groups for a meta-analysis of treatment effect, allowing comparisons of biological and psychological treatments in this specific population.

Effective treatment of this group is vital to achieve the ultimate goal of minimising future victims whilst maximising individual autonomy and minimising financial cost.

References- Ashbeck, L. (2015). Prevalence of mental illness & treatment efficacy among individuals convicted of sexual offenses.

- American

Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM) (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric

Association.

- Assumpcao, A. A., Garcia, F. D., Garcia, H. D.,

Bradford, J. M., & Thibaut, F. (2014). Pharmacologic treatment of

paraphilias. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 37.

- Bentall, R. P. (1993). Deconstructing the concept of schizophrenia. Journal of Mental Health, 2(3).

- Boles. (2012). A training curriculum for assessing & treating sex offenders with mental illnesses.

- Bonta,

J., & Andrews, D. (2007). Risk-Needs-Responsivity Model for

Offender Assessment and Rehabilitation. Public Safety Canada.

- Bonta,

J., Law, M., & Hanson, K. (1998, March). The prediction of criminal

and violent recidivism among mentally disordered offenders: a

meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 123(2).

- Booth, B. D., & Gulati, S. (2014). Mental illness and sexual offending. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 37.

- Bradford,

J. M., & Pawlak, A. (1993). Effects of cyproterone acetate on

sexual arousal patterns of pedophiles. Archives of Sexual Behavior,

22(6).

- Brinded, P. M., Simpson, A. I., Laidlaw, T. M., Fairley,

N., & Malcolm, F. (2001, April). Prevalence of psychiatric disorders

in New Zealand prisons: a national study. Australian and New Zealand

Journal of Psychiatry, 35(2).

- Clark, L., Tyler, N., Gannon, T.

A., & Michael, K. (2014, July). Eye Movement Desensitisation and

Reprocessing for offence related trauma in a mentally disordered sexual

offender. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 20(2).

- Clarke, C., Tapp,

J., Lord, A., & Moore, E. (2011, July). Group-Work for offender

patients on sex offending in a high security hospital: Investigating

aspects of impact via qualitative analysis. Journal of Sexual

Aggression.

- Dunsieth, N. W., Nelson, E. B., A, B.-L. L.,

Holcomb, J. L., Beckman, D., Welge, J. A., . . . McElroy, S. L. (2004,

March). Psychiatric and legal features of 113 Men convicted of sexual

offences. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 65(3).

- Garrett, T.

(2015). Working with a sexual offender with bipolar disorder. In D. T.

Wilcox, T. Garrett, & L. Harkins (Eds.), Sex Offender Treatment: A

Case Study Approach to Issues and Interventions (pp. 199-221). John

Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Gordon, A. (2015). Retrieved June 25th, 2016, from FORUM on Corrections Research: http://www.csc-scc.gc.ca/research/forum/special/espe_n-eng.shtml

- Harris,

A. J., Fisher, W., Veysey, B. M., Ragusa, L. M., & Lurigio, A. J.

(2010, May). Sex offending & serious mental illness: Directions for

policy & research . Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37(5).

- Hartwell,

S. W. (2004, February). Comparison of offenders with mental illness

only and offenders with dual diagnoses. Psychiatric Services, 55(2).

- Hughes,

G. V., & Hebb, J. (2005, January). Problematic sexual behaviour in a

secure psychiatric setting: Challenges and developing solutions.

Journal of Sexual Aggression, 11(1).

- Kelley, S. M., &

Thornton, D. (2015). Assessing risk of sex offenders with major mental

illness: integrating research into best practices. Journal of

Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 7(4).

- Kingston, D. A.,

Malamuth, N. M., Fedoroff, P., & Marshall, W. L. (2009). The

importance of individual differences in pornography use: theoretical

perspectives and implications for treating sexual offenders. Journal of

Sex Research, 46(2-3).

- Kingston, D. A., Olver, M. E., Harris,

M., Wong, S. C., & Bradford, J. M. (2015). The relationship between

mental disorder and recidivism in sexual offenders. International

Journal of Forensic Mental Health, 14(1).

- Lambie, I., &

Seymour, F. (2006, July). One size does not fit all: Future directions

for the treatment of sexually abusive youth in New Zealand. Journal of

Sexual Aggression, 12(2).

- Langevin, R., Langevin, M., Curnoe,

S., & Bain, J. (2009, March). The prevalence of thyroid disorders

among sexual and violent offenders and their co-occurrence with

psychological symptoms. International Journal of Prisoner Health, 5(1).

- Langstrom,

N., Sjostedt, G., & Grann, M. (2004, April). Psychiatric disorders

and recidivism in sexual offenders . Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research

and Treatment, 16(2).

- Mela, M., & Ahmed, A. G. (2014). Ethics and the treatment of sexual offenders. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 37.

- Perkins,

D. (2010). Cognitive approaches to working with mentally disordered

offenders. In A. Bartlett, & G. McGauley (Eds.), Forensic Mental

Health: concepts, systems, and practice (pp. 201-214). Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

- Phillips, H. K., Gray, N. S., Sophie I, M.,

Taylor, J., Moore, S. C., Huckle, P., & MacCulloch, M. J. (2005,

July). Risk assessment in offenders with mental disorders: Relative

efficacy of personal demographic, criminal history, and clinical

variables. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20(7).

- Sakdalan,

J. A., & Gupta, R. (2014, January). Wise Mind-Risky Mind: A

reconceptualisation of dialectical behaviour therapy concepts and its

application to sexual offender treatment. Journal of Sexual Aggression,

20(1).

- Saleh, F. M., & Guidry, L. L. (2003). Psychosocial

and biological treatment considerations for the paraphilic and

nonparaphilic sex offender. Journal of the American Academy of

Psychiatry and the Law, 31(4).

- Schaffer, M., Jeglic, E. L.,

Moster, A., & Wnuk, D. (2010). Cognitive-Behavioral therapy in the

treatment and management of sex offenders. Journal of Cognitive

Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 24(2).

- Smith, A. D.

(2000, April). Motivation and psychosis in schizophrenic men who

sexually assault women. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 11(1).

- Stinson,

J. D., Becker, J. V., & McVay, L. A. (2015). Treatment progress and

behavior following 2 years of inpatient sex offender treatment: A pilot

investigation of Safe Offender Strategies. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of

Research and Treatment .

- Stinson, J. D., McVay, L. A., &

Becker, J. V. (2016). Posthospitalisation outcomes for psychiatric sex

offenders: Comparing two treatment protocols. International Journal of

Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 60(6).

- Walter, G.

(1991, March). The naming of our species: appellations for the

psychiatrist. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 25(1).

- Willis,

G. M., Yates, P. M., Gannon, T. A., & Ward, T. (2012, July). How to

integrate the Good Lives Model into treatment programs for sexual

offending: An introduction and overview. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of

Research and Treatment .

- Yates, P. M. (2003). Treatment of adult

sex offenders: A therapeutic cognitive-behavioural model of

intervention. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 12(3/4).

Author address

Yvette A. Kelly, MBChB

Mason Clinic Regional Forensic Psychiatry Services

Carrington Road

Point Chevalier, Auckland

New Zealand, 1025

Yvette.kelly@waitematadhb.govt.nz

Susan Hatters Friedman, MD

University of Auckland and

Case Western Reserve University

sjh8@case.edu

|