|

Treatment for convicted adult male sex offenders: an overview of systematic reviews

Paula Corabian, Liz Dennett & Christa Harstall

Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton

[Sexual Offender Treatment, Volume 6 (2011), Issue 1]

Abstract

Background: In countries with developed economies, a common approach to protecting communities from sexual offending is to provide specialized treatment for convicted sex offenders to reduce recidivism. Many psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions are currently in widespread use as sex offender treatment (SOT) options delivered within programs to prevent recidivism or reoffending among convicted adult male sex offenders. A number of systematic reviews (SRs) have already evaluated the evidence from primary research studies on the effectiveness of these interventions.

Methods: A structured overview of SRs published in English since January 1998 was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy delivered within programs to reduce recidivism among convicted adult male sex offenders.

Results: Eight SRs met the inclusion criteria. Evidence from seven moderate-to-high quality SRs suggests that cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) delivered within programs adhering to the risk/need/responsivity (RNR) model has the potential to reduce recidivism. These findings must be tempered as they are mostly based on poor quality primary research. The reviewed evidence was inconclusive as to the components or framework of an effective SOT program or the setting in which a program should be delivered.

Conclusions: This overview provides decision-makers in the SOT field with an accessible, good quality synthesis of the best evidence available on the effectiveness of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy delivered within programs to reduce recidivism among convicted adult male sex offenders. While further research is warranted, the available evidence suggests that CBT delivered within programs adhering to the RNR model represents the most promising approach.

Key words: psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, sexual offending, sex offender treatment, systematic review

Introduction

Sexual offending is both a social problem and a public health issue.(Bijleveld, 2007; Brennan & Taylor-Butts, 2008; Center for Sex Offender Management, 2008) It has become a major challenge for policy makers because of the high human and financial costs to victims and the social and health services, as well as the high public investment in policing, prosecuting and incarcerating sex offenders. In countries with developed economies, a common approach to protecting communities from sexual offending is to provide specialized treatment programs for convicted sex offenders to reduce the likelihood of reoffending.

A variety of sex offender treatment (SOT) interventions delivered within programs of different levels of complexity are part of the management of convicted adult male sex offenders in institutions (prison or in-patient forensic psychiatry settings) or in the community (on probation or parole) (Prentky & Schwartz, 2006; McGrath RJ, Cumming GF, Burchard BL, Zeoli S, & Ellerby L, 2010; Center for Sex Offender Management, 2006). Since many psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions are currently in widespread use to reduce recidivism in this population,(McGrath RJ et al., 2010) there is an expectation that reliable scientific evidence is available to support their effectiveness for this indication. However, there continues to be controversy regarding how well they work and how to achieve an effective reduction of recidivism (risk of reoffending) (Grubin, 2007; Briken, 2007; McGrath RJ et al., 2010; Marshall WL & Marshall LE, 2010; Rice & Harris, 2003a; Rice & Harris, 2003b; Rice, Harris, & Quinsey, 2001).

Many investigators have already reviewed a large number of primary research studies on this topic. Good systematic reviews are particularly helpful for busy decision makers who turn to SOT outcome literature for guidance, because the available primary research evidence has already been found, the quality of that evidence evaluated, and the findings summarized for a specific question of interest. However, not all reviews of SOT outcome studies have been conducted according to a structured methodological approach that ensures the control of systematic errors in the review process. Therefore, there was a need for a scientifically rigorous evaluation of the published systematic reviews to determine the robustness of their results and conclusions and to produce a summary of the best available systematic reviews in one place, allowing their findings to be compared and contrasted.

This paper presents the results obtained from an update of a recently published structured overview.(Corabian P, Ospina M, & Harstall C, 2010) http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/doi/10.1002/da.20687/full-bib26 The main objective of this overview was to collate, evaluate, and synthesize findings from methodologically robust systematic reviews on the effectiveness of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions delivered within programs for convicted adult male sex offenders to reduce sexual/non-sexual recidivism (measured at 2 years or more after completion of SOT). Secondary objectives were to identify the components of an optimal SOT program for this population and to determine if the setting of program delivery affects its results. Results of this overview are intended to inform clinical practice and policy in the SOT field.

Materials and Methods

A comprehensive database search was conducted to locate articles published in English since January 1998. The search was conducted by an information specialist (LD) in January 2009 and updated in February 2011. The databases searched included: MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, The Campbell Collaboration Library, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Databases, PsycINFO, Violence and Abuse Abstracts, Criminal Justice Abstracts, Sociological Abstracts, SocINDEX with Full Text, Social Work Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, and National Criminal Justice Reference Service Abstracts. Internet sites of pertinent agencies, institutions, and departments of corrections and their links were also searched for relevant material. Different combinations of subject headings and keywords (including psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, sexual offending, and sex offender treatment) were used in the database searches to ensure that relevant material was not missed. A detailed description of the search strategy (including the search terms and keywords used) is available upon request.

Contacts were made with Canadian experts in the SOT field to identify unpublished literature. In addition, the bibliographies of the retrieved full text articles were examined for relevant references that might have been missed in the database searches.

Two reviewers independently selected the systematic reviews using a predefined set of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Considered for inclusion were reviews that by virtue of design and quality of reporting were most likely to provide the best evidence. Based on the description by Cook and colleagues,(Cook DJ, Sackett DL, & Spitzer WO, 1995) a review was selected to formulate the evidence base for this overview if it met all of the following criteria: 1) focused research question; 2) explicit search strategy; 3) explicit, reproducible, and uniformly applied criteria for study selection; 4) critical examination of the included studies to explore the methodological quality differences as an explanation for heterogeneity in study results; and 5) qualitative or quantitative data synthesis.

Systematic reviews were included if they reviewed comparative or controlled studies reporting on: - Population - adult male sex offenders (18 years and older) convicted of a sexual offence;

- Intervention(s) - psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy (alone or combined), provided in inpatient and/or outpatient settings;

- Comparator(s) - no therapy, placebo, usual care, other therapy (e.g., surgical therapy; alternate therapy, less intensive, and/or less specific therapy); and

- Outcome - violent or nonviolent, sexual or nonsexual recidivism defined as the number of convictions for violent or nonviolent (re)offences, number of convictions for (re)offences with or without sexual element.

For the purpose of this overview, a sexual offence was defined as an officially recorded sexual misbehaviour or criminal behaviour with sexual intent that results in some form of criminal justice intervention or official sanction.(Harris, Phenix, Hanson, & Thornton, 2003) Only sexual offences against an identifiable victim, such as a child or a non consenting adult victim (category "A" in the STATIC-99), were considered in this review.(Harris et al., 2003) Internet-related sexual offences were also considered.

Only full text, peer-reviewed, articles were considered for inclusion in this overview. In the case of duplicate or multiple publications, only the most recent and complete version was included. Studies conducted in countries other than Canada, the United States of America, Australia, New Zealand, and European Union countries were not included.

Data on study characteristics, targeted populations, interventions, and outcomes were extracted from the selected systematic reviews by one reviewer using predefined data extraction forms. Data extraction was verified by a second reviewer.

Two reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of the selected systematic reviews using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) tool. The AMSTAR tool is a validated checklist(Shea et al., 2007; Shea et al., 2010) that evaluates the overall quality of systematic reviews by using eleven criteria that address important methodological domains. For a criterion to have been 'met', it must be scored as 'yes'. Based on a summary of the criteria met, each review was labeled as "high quality" (score eight to eleven), "moderate quality" (score four to seven), or "low quality" (score zero to three).

Disagreements on quality assessments between reviewers were resolved by discussion until consensus was reached. The degree of the difference or equivalence between the two reviewers was not measured and a statistical measure of the inter-rater agreement was not provided, as consensus was required to finalize the critical appraisal results for each of the selected studies. When consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted to critically appraise the quality of the selected systematic reviews.

Systematic reviews rated as "low quality" were excluded from data analysis and synthesis.

Evidence from the moderate to high systematic reviews was qualitatively synthesized and presented in summary tables.

Results

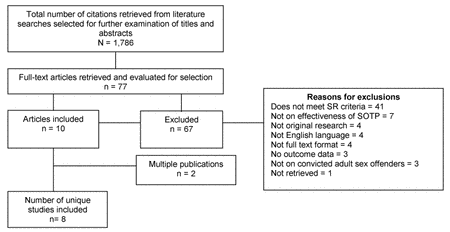

The literature searches identified 1,786 citations. After screening titles and abstracts, the full text articles of 77 potentially relevant studies were retrieved and further evaluated for inclusion in the overview. The application of the selection criteria to the 77 full text articles resulted in ten studies(Brooks-Gordon B, Bilby C, & Wells H, 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson, Bourgon, Helmus, & Hodgson, 2009; White, Bradley, Ferriter, & Hatzipetrou, 2000; Aos, Miller, & Drake, 2006; Bilby, Brooks-Gordon, & Wells, 2006; Polizzi, MacKenzie, & Hickman, 1999; Losel & Schmucker, 2005; Hanson RK, Bourgon G, Helmus L, & Hodgson S, 2009) that were considered for inclusion. Two systematic reviews (Losel & Schmucker, 2005; Hanson RK et al., 2009) were identified as multiple publications of two other systematic reviews (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2009). Multiple publications were not considered as unique studies, although any additional information that they provided was included. Therefore, this overview selected eight systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) to formulate the evidence base for the effectiveness of SOT programs among male sex offenders.

The list of the 67 excluded studies and reasons for their exclusion are available upon request. The full study selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1: Study selection process |

Characteristics of the selected systematic reviews

The characteristics of the selected systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) are summarized in  Table 1. Table 1.

Of the eight systematic reviews included in this overview, four were conducted by reviewers from North America (Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) and four by reviewers from Europe and Australia (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; White et al., 2000; Bilby et al., 2006). Their objectives and selection criteria varied and, as a result, there was little overlap among them regarding the primary research studies that they included. Only papers reporting results from the long-term randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by Romero in the 1970s and papers reporting preliminary and final findings from the California's Sex Offender Treatment and Evaluation Project (SOTEP) study (also a long-term RCT) were included in most of the systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999).

The number of published and unpublished primary research studies included in the selected systematic reviews ranged from three (White et al., 2000) to sixty-nine (Schmucker & Losel, 2008). All systematic reviews included controlled or comparative studies (reported between 1953 and 2009) that evaluated the effect of various psychotherapy interventions. Comparison groups included no treatment, standard care, pharmacotherapy/drug treatment, "treatment as usual", alternate treatment, or treatment refused. One systematic review (Schmucker & Losel, 2008) also included studies that evaluated the effect of pharmacotherapy on recidivism rates. Primary research was mostly based on American and Canadian samples. There was considerable variation at the primary research level on how SOT interventions were classified, the types of sex offenders involved, and the definition of outcomes. Only a few of the included primary research studies used rigorous/strong research design.

Most of the treatment programs evaluated in the primary research studies were developed and implemented before the mid 1980s. Primary research involved a heterogeneous group of individuals convicted for different types of sexual offences. Child molestation was the most frequently addressed sexual offence, followed by rape, and only a few primary studies included adult exhibitionist and voyeuristic crimes. Most systematic reviews provided little or no information on the characteristics of the offenders involved in their included primary research studies. None reported separate results on the effectiveness of any SOT interventions for different sex offender typologies.

The majority of systematic reviews did not provide relevant details about the programs evaluated at the primary research level (e.g., treatment concept; duration; selection criteria; risk assessment procedures and tools; type, frequency, and duration of sessions; timing of treatment; and treatment providers). Recidivism was measured by reconviction, reoffending, reincarceration, or re-arrest in most primary research studies using a variety of definitions (e.g., return to prison, readmissions to institutions, parole violations, unofficial community reports, or all of these) and data sources (e.g., criminal justice records, state/provincial records, child protection records, self-reports, or all of these).

No systematic review reported on adverse events for any of the interventions they evaluated.

Methodological characteristics and quality of the selected systematic reviews

All systematic reviews used multiple electronic databases in their literature searches and other sources to locate the most relevant primary research ( Table 1). However, all except two (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006) limited the literature search and study selection by language of publication. One systematic review (Schmucker & Losel, 2008) searched for studies reported in five languages (English, French, German, Dutch, and Swedish), one (Hanson et al., 2002) searched for studies published in English and French, and in another one (Hanson et al., 2009) researchers reviewed studies reported in English, French, and German. It appears that study selection in three systematic reviews (White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) was restricted to those reported in English. The likelihood of publication bias was assessed only in three systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; White et al., 2000). Most systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006) provided a detailed description of their selection criteria in terms of participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design. Table 1). However, all except two (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006) limited the literature search and study selection by language of publication. One systematic review (Schmucker & Losel, 2008) searched for studies reported in five languages (English, French, German, Dutch, and Swedish), one (Hanson et al., 2002) searched for studies published in English and French, and in another one (Hanson et al., 2009) researchers reviewed studies reported in English, French, and German. It appears that study selection in three systematic reviews (White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) was restricted to those reported in English. The likelihood of publication bias was assessed only in three systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; White et al., 2000). Most systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Bilby et al., 2006) provided a detailed description of their selection criteria in terms of participants, interventions, comparators, outcomes, and study design.

The standards for scientific rigour used for the selection and analysis of primary research studies varied across the selected systematic reviews. Three systematic reviews used the Maryland Scale of Scientific Rigor or a 5-point rigour scale adapted from this scale (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999). Two systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; White et al., 2000) used the guidelines from the Cochrane Collaboration and one (Hanson et al., 2009) made decisions regarding study quality based on the guidelines of the Collaborative Outcome Data Committee (CODC). Consequently, these systematic reviews often disagreed in terms of which primary research studies they identified to be rigorous or good enough to be included.

Four systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000) reported that data extraction from primary research studies was performed by two independent reviewers, whereas three (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000) reported that two reviewers had independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies. Four systematic reviews (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; Aos et al., 2006) analyzed and synthesized the evidence both qualitatively and quantitatively. Because of the large degree of heterogeneity in terms of study design, participants, interventions, and outcome measures in the reviewed primary research, these four systematic reviews conducted statistical analyses of study heterogeneity for their pooled data and moderator analyses.

The conclusions of all systematic reviews were consistent with the reported results and they all highlighted the need for further research and more rigorous evaluations of SOT interventions.

Methodological quality varied across the selected systematic reviews ( Table 2). One systematic review (Bilby et al., 2006) was rated as "low quality", four (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Hanson et al., 2002; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) as "moderate quality", and three (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000) as "high quality". Table 2). One systematic review (Bilby et al., 2006) was rated as "low quality", four (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Hanson et al., 2002; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) as "moderate quality", and three (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000) as "high quality".

The seven systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) rated as moderate- and high-quality on the AMSTAR tool, qualified for data analysis and synthesis. Their findings are summarized in the following commentary and in  Table 3. Table 3.

Findings from seven moderate-to-high quality systematic reviews

During the late 1990s White and colleagues (White et al., 2000) conducted a Cochrane systematic review on anti-libidinal treatment for adults who have been convicted of sexual offences or who have disorders of sexual preference. They included three RCTs, which were also reviewed by Brooks-Gordon and colleagues (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006) who, in 2006 reported the results from the most comprehensive search for experimental research in the area of sexual offending. Brooks-Gordon and colleagues qualitatively reviewed data from nine RCTs (all reported before 1998) as part of a systematic review of the literature on psychological interventions for adult sexual offenders and adult individuals showing abusive sexual behaviours.

Of all experimental research included in these two systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; White et al., 2000), the RCT on group psychotherapy (conducted in the community by Romero and Williams during 1970s) is the only RCT that reported data of interest for this overview (data on recidivism measured over a follow-up period of 2 years or more for all offenders) ( Table 3). Results reported by this RCT did not show group psychotherapy (CBT in group) to be beneficial in reducing re-arrest rates and even suggested the potential for harm at 10-year follow-up. Group psychotherapy plus probation increased the re-arrest rate by 10 years when compared to standard care. However, there was no significant difference in re-arrest rates for those allocated to group psychotherapy plus probation (14%) and those receiving standard care (7%) (odds ratio [OR] = 1.87, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8 to 4.37). Table 3). Results reported by this RCT did not show group psychotherapy (CBT in group) to be beneficial in reducing re-arrest rates and even suggested the potential for harm at 10-year follow-up. Group psychotherapy plus probation increased the re-arrest rate by 10 years when compared to standard care. However, there was no significant difference in re-arrest rates for those allocated to group psychotherapy plus probation (14%) and those receiving standard care (7%) (odds ratio [OR] = 1.87, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.8 to 4.37).

In 1999 Polizzi and colleagues (Polizzi et al., 1999) published the results of a systematic review of sex offender prison- and non-prison-based treatment programs. Of all 21 studies that were assessed, the reviewers included 13 impact evaluation studies that were completed within 10 years before 1999 (however, the treatment might have been developed and implemented earlier). The included 13 studies (eight studies on prison-based treatment and five studies on non-prison-based treatment) varied with regard to the type of sex offender population (e.g., child molesters, high-risk offenders, adult rapists, and exhibitionists) and the outcome measures used (e.g., sexual recidivism or nonsexual recidivism). Recidivism was determined as a re-arrest for sexual, felony, or violent offences and as re-conviction for a sexual offence, non-sexual offence, or violent offence. Most treatment programs were not sufficiently described and relevant offenders' characteristics were not provided.

Only two studies examining prison-based treatment and four non-prison-based treatment studies were judged by Polizzi et al. (Polizzi et al., 1999) as sufficiently rigorous (level 3 or above on Mariland scale) and the reviewers used their results to draw conclusions ( Table 3). Based on these data, non-prison based SOT programs using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) were deemed to be effective in reducing sexual offense recidivism among sex offenders. Prison-based SOT programs were judged as promising approaches as the evidence was not strong enough to support a conclusion that were effective in reducing recidivism. Table 3). Based on these data, non-prison based SOT programs using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) were deemed to be effective in reducing sexual offense recidivism among sex offenders. Prison-based SOT programs were judged as promising approaches as the evidence was not strong enough to support a conclusion that were effective in reducing recidivism.

Hanson and colleagues (Hanson et al., 2002) conducted a meta-analysis that combined data from 68 outcome studies on 43 treatment programs using psychological interventions, involving more than 9,000 treated and untreated or differently treated sex offenders ( Table 3). The majority of comparisons involved only adult sex offenders. The evaluated interventions were delivered between 1965 and 1999, mostly in specialized SOT programs, with approximately 80% of the offenders receiving "current" treatment (CBT offered after 1980 or behavioural, other psychotherapeutic, and/or mixed treatments delivered between 1998 and 2000). Recidivism was defined by re-conviction in eight studies, re-arrest in 11, and 20 studies used broad definitions, including parole violations, readmissions to institutions, unofficial community reports, or all of these. The average follow-up periods ranged from 12 months to 16 years, with a median follow-up period of 46 months for both treatment and comparison groups. Table 3). The majority of comparisons involved only adult sex offenders. The evaluated interventions were delivered between 1965 and 1999, mostly in specialized SOT programs, with approximately 80% of the offenders receiving "current" treatment (CBT offered after 1980 or behavioural, other psychotherapeutic, and/or mixed treatments delivered between 1998 and 2000). Recidivism was defined by re-conviction in eight studies, re-arrest in 11, and 20 studies used broad definitions, including parole violations, readmissions to institutions, unofficial community reports, or all of these. The average follow-up periods ranged from 12 months to 16 years, with a median follow-up period of 46 months for both treatment and comparison groups.

Averaged across all types of treatments and research designs, the findings indicated an overall positive effect of treatment versus no treatment in terms of sexual recidivism rates (12% versus 17%) and general (any) recidivism rates (28% versus 39%) (Hanson et al., 2002). The treatments that appeared to be effective were CBT approaches for adults and systemic treatments for adolescents. Most of the evidence for treatment effectiveness came from incidental assignment studies which, on average, were associated with significant reductions in sexual recidivism (OR = 0.62, 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.77, 17 studies, N = 2,948) and in general recidivism (OR = 0.52, 95% CI: 0.40 to 0.68, 10 studies, N = 1,176). Overall, the only four random-assignment studies were associated with non-significant odd ratios for both sexual (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.67 to 1.59, three studies, N = 694) and general recidivism (OR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.69 to 1.22, four studies, N = 897). Treatment effect on sexual recidivism was much stronger in 17 unpublished studies (OR = 0.65, 95% CI: 0.52 to 0.81) than in 21 published studies (OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.79 to 1.15). However, similar results for general recidivism were showed by the 16 published studies (OR = 0. 59, 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.70) and the 15 unpublished studies (OR = 0.54, 95% CI: 046 to 0.64).

When data from random- and incidental-assignment studies were combined, "current" treatments were associated with significant reductions in both sexual (from 17.3% to 9.9%) and general recidivism (from 51% to 32%) for adult and adolescent sex offenders whereas the "older" treatments appeared to have little effect (Hanson et al., 2002). According to the Hanson and colleagues, "these reductions were not large, but they were statistically reliable and large enough to be of practical significance" (Hanson et al., 2002). However, the reviewers advised on interpreting the findings with caution, given the small number of studies and the significant variability across these studies.

Both "current" institutional and community treatments for adult sex offenders appeared to be effective in terms of reduced sexual recidivism and reduced general recidivism ( Table 3) (Hanson et al., 2002). Institutional and community treatments for adults showed similar results for sexual recidivism. However, treatments for adults delivered in the community appeared to have a stronger effect on general recidivism than treatment provided in institutions. Four studies (one random-assignment and three incidental-assignment studies) of sex offender specific treatment for adults found a significant reduction in general recidivism (OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.82, Q = 32.79; P <0. 001). Table 3) (Hanson et al., 2002). Institutional and community treatments for adults showed similar results for sexual recidivism. However, treatments for adults delivered in the community appeared to have a stronger effect on general recidivism than treatment provided in institutions. Four studies (one random-assignment and three incidental-assignment studies) of sex offender specific treatment for adults found a significant reduction in general recidivism (OR = 0.61, 95% CI: 0.45 to 0.82, Q = 32.79; P <0. 001).

According to Hanson and colleagues (Hanson et al., 2002) "studies comparing treatment completers to dropouts consistently found higher sexual and general recidivism rates for the dropouts, regardless of the type of treatment provided. Even in studies where there was no difference between the treatment group and the untreated comparison groups, the treatment dropouts did worse". The reviewers also reported that "offenders who refused treatment were not at higher risk for sexual recidivism than offenders who started treatment. Treatment refusers, however, were at relatively high risk for general recidivism" (Hanson et al., 2002). Offenders assigned to treatment based on perceived need had significantly higher sexual recidivism rates than those considered not to need treatment and showed similar general recidivism rates for both treated and untreated groups.

Aos and colleagues (Aos et al., 2006) conducted a systematic review on correction programs for adult offenders, including SOT programs, to determine what works, if anything, to lower recidivism rates. Of the 291 primary research studies that met their standards for scientific rigor, 18 were outcome evaluation studies (ten of which were published before 1998) of various adult SOT programs. Most SOT programs were not sufficiently described and no relevant information was provided on the involved offenders' characteristics. Eleven SOT programs (located in prison or in the community) provided specialized CBT and reported significant reductions in recidivism ( Table 3). Data pooled from five studies indicate that specialized CBT programs provided within a prison setting (which may also include behavioural reconditioning to discourage deviant arousal and modules addressing RP) for adult sex offenders achieve, on average, a statistically significant 14.9% reduction in recidivism rates compared with "treatment as usual". Table 3). Data pooled from five studies indicate that specialized CBT programs provided within a prison setting (which may also include behavioural reconditioning to discourage deviant arousal and modules addressing RP) for adult sex offenders achieve, on average, a statistically significant 14.9% reduction in recidivism rates compared with "treatment as usual".

Data pooled from six studies indicate that specialized CBT programs provided in the community for low-risk adult sex offenders on probation achieve, on average, a statistically significant 31.2% reduction in recidivism rates compared to "treatment as usual" (Aos et al., 2006). These community-based CBT programs were described as being similar to the specialized CBT programs provided in prison. Data pooled from the other seven studies showed that the evaluated SOT programs (providing psychotherapy, behavioural therapy, or mixed treatments, for which the location was not clearly identified) did not demonstrate a statistically significant reduction in recidivism compared to "treatment-as-usual" ( Table 3). Table 3).

Schmucker and Losel (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Schmucker & Losel, 2005) conducted the first meta-analysis of both published and unpublished sex offender psychological and physical treatment (including hormonal treatment) outcome studies reported in five languages. They reviewed 69 studies with more than 22,000 subjects using 80 independent comparisons between treated and untreated sex offenders ( Table 3). About one-third of these studies were reported since 2000, but the actual program implementation started earlier (1990s). Unpublished evaluations comprised 36% of the study pool. The majority of comparisons involved only adult sex offenders. Most programs combined offenders convicted for different sex offences, most frequently involving child molesters, followed by rapists and exhibitionists. However, the description of offenders' characteristics in the included primary research was often insufficient, and only some studies differentiated the results by type of sexual offence. Table 3). About one-third of these studies were reported since 2000, but the actual program implementation started earlier (1990s). Unpublished evaluations comprised 36% of the study pool. The majority of comparisons involved only adult sex offenders. Most programs combined offenders convicted for different sex offences, most frequently involving child molesters, followed by rapists and exhibitionists. However, the description of offenders' characteristics in the included primary research was often insufficient, and only some studies differentiated the results by type of sexual offence.

Nearly one-half of the comparisons addressed CBT programs (46%) and 14 comparisons addressed physical treatment, six of which dealt with hormonal medication (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005) Although most treatments were specifically designed for sex offenders ( Table 3), the reviewers found it difficult to rate whether treatment was implemented reliably, as three-quarters of the studies (49 comparisons) did not provide information on program integrity. Approximately one-half of the comparisons took place in an institutional setting. A group format was most frequently used. However, almost 50% of the programs included at least some individualized treatment. An explicit extension of treatment through specific after-care services was reported for 15 comparisons. The definition of recidivism (recorded after an average follow-up of more than 5 years ) varied from arrest (24%), conviction (30%), and charges (19%), to lapse behaviour (4%). Table 3), the reviewers found it difficult to rate whether treatment was implemented reliably, as three-quarters of the studies (49 comparisons) did not provide information on program integrity. Approximately one-half of the comparisons took place in an institutional setting. A group format was most frequently used. However, almost 50% of the programs included at least some individualized treatment. An explicit extension of treatment through specific after-care services was reported for 15 comparisons. The definition of recidivism (recorded after an average follow-up of more than 5 years ) varied from arrest (24%), conviction (30%), and charges (19%), to lapse behaviour (4%).

Results of an analysis that integrated the individual effect sizes according to the random-effect model showed that the absolute difference in sexual recidivism between treatment and control groups was 6.4 percentage points (a 37% reduction from the base rate of the control group) (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel& Schmucker, 2005). Programs that specifically addressed adult sex offenders, had a significant effect on sexual recidivism ( Table 3). For violent recidivism, the average recidivism rate for treated offenders was 5.2 percentage points lower than that for untreated offenders (a 44% reduction from the base rate of the control group). The corresponding rate of general recidivism for treated offenders was 11.1 percentage points lower than for untreated offenders (a 31% reduction from the base rate of the control group). Except for violent recidivism, the effect size distributions showed considerable heterogeneity. Table 3). For violent recidivism, the average recidivism rate for treated offenders was 5.2 percentage points lower than that for untreated offenders (a 44% reduction from the base rate of the control group). The corresponding rate of general recidivism for treated offenders was 11.1 percentage points lower than for untreated offenders (a 31% reduction from the base rate of the control group). Except for violent recidivism, the effect size distributions showed considerable heterogeneity.

To isolate treatment characteristics and offender characteristics as variables that might account for these differences, the reviewers conducted moderator analyses (restricted to sexual recidivism as an outcome) (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005). Type of treatment was one feature that moderated the outcomes. The various treatment approaches differed considerably in their effect size on sexual recidivism and only hormonal treatment, CBT and classic behaviour therapy had significant impact ( Table 3) (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005). Table 3) (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005).

The setting variable revealed no significant difference. (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005) However, there was a strong tendency for relatively larger effects on sexual recidivism for outpatient treatment (OR = 1.93, 95% CI: 1.35 to 2.77; evaluated in 27 comparisons) and smaller effects for institution-based treatments (OR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.84 to 1.60, not statistically significant for prison-based programs evaluated in 21 comparisons; OR = 1.10, 95% CI: 0.62 to 1.94, not statistically significant for hospital-based programs evaluated in eight comparisons). Mixed settings (10 comparisons) had an intermediate effect size (OR = 1.37, 95% CI: 0.78 to 2.41, not statistically significant).

Although the decade in which a program was implemented related significantly to the effect size, no linear relationship was found.(Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005) More "modern" programs did not generally prove to be particularly successful (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.86 to 1.87, not statistically significant for treatments implemented in the 1990s; OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.77, for treatments implemented in the 1980s; OR = 2.03, 95% CI: 1.34 to 3.09, for treatments implemented in the 1970s; OR = 0.56, 95% CI: 0.32 to 0.98, for treatment implemented before 1970). The year of publication as another indicator of recency showed similar results (r = 0.08, P = 0.51).

Whether treatment was completed or terminated prematurely had an impact on sexual recidivism, with completers showing better effects than the control groups (OR = 1.58, 95% CI 1.23 to 2.05, for treatment completed regularly) (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005). However, dropouts did significantly worse (OR = 0.51, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.67). Dropping out of treatment doubled the odds of relapse, and this effect was homogeneous (Q = 11.52, P = 0.57). In contrast, the effect size that referred to completers revealed considerable heterogeneity (Q = 100.20; P < 0.001).

Overall, study design quality did not yield a significant moderator effect (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005). There was no linear relationship between design quality and the effect size (r = 0.11, P = 0.36) and RCTs did not differ from the other study designs (OR = 1.48, 95% CI: 0.74 to 2.96). The length of follow-up did not correlate with the effect size (r = 0.00). Neither did different indicators of reoffending (i.e., reconviction, re-arrest, etc.) relate systematically to outcome variation (Q = 3.45, P = 0.49). Sample size had a clear relation to the effect size (r = -0.26, P = 0.03) that resulted mainly from large treatment effects in trials with very small samples (N ≤ 50) and could not be attributed to a publication bias only. Features of descriptive validity were also related to effect size. In particular, a lack of reporting details on the treatment concept and on outcome statistics correlated significantly with the effect size (r = -0.33, P < 0.001; and r = -0.24, P = 0.03). Although no significant difference was found between the findings from published and unpublished studies, a significant mean treatment effect appeared in published studies only (N = 40, OR = 1.62, 95% CI: 1.23 to 2.13).

Hanson and colleagues(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) recently conducted a meta-analysis of 23 SOT outcome studies. The primary question was whether the "what works" principles of effective correctional interventions for general offenders (risk/need/responsivity [RNR]) also apply to psychological treatment for sexual offenders. A secondary objective was to assess the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sexual offenders using only studies that met a minimum level of study quality established by the CODC guidelines and examine the extent to which the study results varied based on study design. The reviewers originally planned to assess both psychological and physical interventions, but none of the surgery or pharmacotherapy studies met the minimum standard of acceptability.

Most of the included primary research studies were based on Canadian or American samples and were focused on adult male sex offenders.(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Of the 23 programs, 10 were offered in institutions, 11 in the community, and two in both settings. Treatment was delivered between 1965 and 2004, with approximately 90% of the offenders receiving treatment after 1980 (most studies were reported between 1980 and 2009). Fourteen of the 16 studies reported after 1998 examined specialized treatment programs for sex offenders. Recidivism was defined as reconviction in 10 studies and re-arrest in 12 studies, and the most common source of recidivism information was national criminal justice records, followed by state or provincial records. The average follow-up periods ranged from 1 to 21 years (median of 4.7 years).

The extent to which each of the 23 programs evaluated in the primary research adhered to the RNR principles was rated based on all available information, including program manuals, research articles, reports of accreditation panels, and, in some cases, site visits.(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Programs were rated as adhering to the "risk" principle if they provided intensive interventions to higher risk offenders and little or no treatment to low-risk offenders. Adherence to the "need" principle was met if the primary treatment targets were among those reported as being significantly related to sexual or general recidivism in previous meta-analyses. Programs were considered to meet the "responsivity" principle when they provided treatment in a manner and style matched to the learning style of the offenders.

Hanson and colleagues found that the sexual, violent (including sexual), and general recidivism rates for the treated sexual offenders were lower than the rates observed for the comparison groups (based on unweighted averages, 10.9% versus 19.2% for sexual recidivism; 22.9% versus 32% for sexual or violent recidivism; and 31.8% versus 48.3% for general recidivism).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Confidence in these findings was tempered by the observation that most studies used "weak" research designs. Of the included 23 studies, 18 were rated as weak and five were rated as good, and the effects tended to be stronger in the weak research designs compared to the good research designs.

Results from both fixed-effect and random-effects analyses indicated significantly lower sexual recidivism rates in the treatment groups than in the comparison groups ( Table 3).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Treatment appeared to be effective for adults, and did not depend on whether the program was delivered in the community or institution (both fixed-effect and random-effect comparisons showed no significant differences). Using a fixed-effect model, the treatment effects were smaller in the good-quality studies (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.20) than the weak studies (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.81). This comparison was not significant using random-effect comparisons. No significant differences were noted in the treatment effects for published or unpublished studies. Table 3).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Treatment appeared to be effective for adults, and did not depend on whether the program was delivered in the community or institution (both fixed-effect and random-effect comparisons showed no significant differences). Using a fixed-effect model, the treatment effects were smaller in the good-quality studies (OR = 0.94, 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.20) than the weak studies (OR = 0.64, 95% CI: 0.51 to 0.81). This comparison was not significant using random-effect comparisons. No significant differences were noted in the treatment effects for published or unpublished studies.

According to both fixed- and random-effect analyses, the violent (including sexual) recidivism rates were not significantly lower for the treatment groups relative to the comparison groups ( Table 3).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) There were no differences in the effects according to whether the studies involved adults or adolescents, or were delivered in the community or in an institution. There were no differences in the effects according to whether the studies were published or unpublished. Table 3).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) There were no differences in the effects according to whether the studies involved adults or adolescents, or were delivered in the community or in an institution. There were no differences in the effects according to whether the studies were published or unpublished.

Results from both fixed- and random-effect analyses indicated that the general (any) recidivism rate was statistically significantly lower in the treatment groups than in the comparison groups ( Table 3). (Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Treatment appeared to be effective for adults. There were no differences in the treatment effects according to whether the research design was good or weak, whether the study was published or unpublished, or whether the treatment was delivered in the community or in an institution. Table 3). (Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson RK et al., 2009) Treatment appeared to be effective for adults. There were no differences in the treatment effects according to whether the research design was good or weak, whether the study was published or unpublished, or whether the treatment was delivered in the community or in an institution.

According to Hanson and colleagues(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) their results suggest that the RNR principles are relevant to the treatment of sexual offenders. The pattern of results was consistent with the direction predicted by the RNR principles "in both the full set of included studies as well as in the published studies with better design".(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) When adherence to the RNR principles was considered, there was relatively little residual variability. Programs that did not adhere to any of the principles had consistently low treatment effects. For programs adhering to all three principles, the treatment effects were consistently large. Only for programs adhering to two principles the variability was significant.

For the reduction of sexual recidivism , fixed-effect comparisons showed that programs were more effective if they targeted criminogenic needs (need principle) and were delivered in a manner that was likely to engage the offenders (responsivity principle).(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) The OR values for the high-risk samples were not significantly different than those for the other samples, although, according to the reviewers, the direction of the treatment effect was consistent with the risk principle, with stronger treatment effects for the high risk offenders. For the reduction of violent (including sexual) recidivism, there were no significant differences based on adherence to RNR principles although, according to the reviewers, all effects were in the expected directions.For the reduction of general (any) recidivism, the fixed-effect model found stronger effects for treatments adhering to the responsivity principle as well as for treatments adhering to all three principles. According to the reviewers, all the effects were in the direction predicted by the RNR principles, although none were statistically significant using the random-effect model.

Hanson and colleagues(Hanson et al., 2009; Hanson RK et al., 2009) reported that recent treatments were more effective, on average, than the treatments delivered in previous decades. The starting date for the treatment ranged between 1965 and 1997 (M = 1,986, SD = 8.5 years, median of 1989). For all outcomes, the linear association was statistically significant for both the fixed- and random-effects models.

Discussion

The number of SOT programs has grown during the past decade and treatment for convicted adult males sex offenders has evolved as progress was made in the "what works" literature for general offenders.(Grubin, 2007; McGrath RJ et al., 2010) The SOT field has developed increasingly elaborate theories, classification systems, and specialized interventions to understand and treat these individuals. Despite this growth, research on the impact of SOT interventions and programs has been slow to mature, and results have often been contradictory. Accordingly, the perceived value of SOT interventions and programs and the views on how best to manage adult male sex offenders have been inconsistent.

By synthesizing the evidence from seven moderate-to-high quality systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) this overview provides useful information on the current SOT practice and possible markers for effective programs.

Which of the available SOT interventions and programs are effective?

Although considerable research has addressed this question, the debate on the effectiveness of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy interventions delivered within programs to reduce the risk of recidivism among adult male sex offenders still remains ( Table 3). Five systematic reviews (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) concluded that psychological treatment using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches reduces the risk of recidivism in this population whereas the authors of two systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; White et al., 2000) concluded that the evidence is insufficient to draw such a conclusion. Table 3). Five systematic reviews (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999) concluded that psychological treatment using cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches reduces the risk of recidivism in this population whereas the authors of two systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; White et al., 2000) concluded that the evidence is insufficient to draw such a conclusion.

Most systematic reviews suggest a positive effect for CBT on both sexual and general recidivism. However, methodological problems, inconsistent results, and the small number of high-quality primary research studies included in these systematic reviews raise uncertainty about which of the available CBT approaches work for this population. Therefore the answer to the question, "Does SOT using CBT approaches work?" is a cautious "Yes" as, overall, the best available evidence shows small but statistically significant reductions in sexual and general recidivism rates among adult male sex offenders after undergoing CBT.

The most recently published high-quality systematic review by Hanson and colleagues (Hanson et al., 2009) reported that psychological treatments implemented or delivered after 1980s showed stronger effects than older treatments. This finding is consistent with the finding by Hanson et al.(Hanson et al., 2002), but different from that by Losel and Schmucker (Losel & Schmucker, 2005), who reported in 2005 that the most effective treatments were those implemented/delivered in the 1970s. The different findings may be partially attributed to the selection criteria and standards for scientific rigour used in these systematic reviews.

Given the presence of various potentially confounding factors and the methodological problems of the primary research studies included in the seven moderate-to-high quality systematic reviews, it was not possible to confidently draw conclusions on which specific CBT approach works for whom and under what circumstances. Only two relevant RCTs were evaluated in all systematic reviews: the RCT conducted in a community setting by Romero and the RCT conducted in a hospital setting as part of the SOTEP project. Findings from these two RCTs do not necessarily support the efficacy of treating convicted adult male sex offenders with group psychotherapy and with CBT approaches (including RP techniques). However, the programs evaluated by these RCTs were developed and delivered during the 1970s and 1980s. The design and implementation of these programs predated the advances in research and practice in the SOT field, and therefore the findings reported by the two RCTs, considered within the context of the more recent developments, may be less than optimal.

Although hormonal treatment showed encouraging results in the meta-analysis by Schmucker and Losel, according to the reviewers "it is necessary to collect more solid knowledge on circumstances and modes that may prove hormonal treatment to be reasonable" (Schmucker & Losel, 2008)

What are the optimal SOT programs for convicted adult male sex offenders?

A large number of SOT programs using various CBT approaches for adult males convicted for different types of sexual offences were evaluated in the primary research included in the selected systematic reviews (Brooks-Gordon B et al., 2006; Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009; White et al., 2000; Aos et al., 2006; Polizzi et al., 1999). However, since the evaluated programs were not sufficiently documented and little information was provided on the involved offenders' characteristics and who delivered or provided the therapy, it was not possible to identify which elements contributed more or less to the success or failure of a program and who of the treated offenders were most likely to benefit from or be harmed by treatment.

Three systematic reviews (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson et al., 2009) conducted separate analyses to determine which of the treatment and sex offender characteristics were likely to moderate the treatment effects observed in their primary research studies. However, these reviews evaluated heterogeneous modes of treatment and their findings were reported differently in terms of the outcome of interest (which was defined and measured differently). They did not reach similar conclusions for some of the evaluated characteristics, and their reported findings did not allow a sub-group analysis to determine which SOT program is more effective, who is likely to benefit the most, and under what circumstances.

In the most recently published high-quality systematic review(Hanson et al., 2009) programs using psychological interventions that adhered to the RNR principles showed the largest reductions in sexual and general recidivism. Based on their results, Hanson and colleagues considered that the principles of risk (treatment intensity is matched to the offender's level of risk), need (criminogenic needs are targeted for treatment), and responsivity (treatment is sensitive to the offenders' learning style) should be a primary consideration in the design and implementation of SOT programs using CBT (Hanson et al., 2009). The reviewers suggested that policy-makers and researchers concerned with improving quality of SOT programs would benefit from carefully considering the importance of "selecting staff based on relationship skill, using treatment manuals, training staff, and starting small".

According to Hanson and colleagues, most contemporary SOT programs using CBT already conform to some aspects of the "responsivity" principle; however, many do not meet the test for the "need" principle (Hanson et al., 2009). Attention to this principle would motivate the largest changes in the therapeutic interventions currently offered to sexual offenders. The reviewers also mentioned that, although much remains to be known about how best to apply the "risk" principle to sexual offenders, treatment providers should be aware that noticeable reductions in recidivism are not to be expected among the lowest risk offenders. Other treatment goals, such as meaningful reintegration into the community, may be appropriate for these cases.

Does the setting of the SOT programs affect their impact on the outcomes of interest?

The selected systematic reviews reached slightly different conclusions on the impact of setting on the outcomes of interest. Of the three systematic reviews that analyzed setting or location of the program as a variable that might account for changes in treatment effect, two reported that the setting did not moderate the treatment effect (Hanson et al., 2002; Hanson RK et al., 2009), while the third review (Schmucker & Losel, 2008; Losel & Schmucker, 2005) reported a trend for larger treatment effect in outpatient settings compared to in-patient settings . According to Hanson et al., the available literature on SOT "does not provide strong tests of whether program location matters, given that no studies have directly compared the same treatment in both settings".(Hanson et al., 2009)

Strengths and limitations of the overview

This overview brought together a large body of evidence and allowed the findings of separate methodologically rigorous systematic reviews on SOT programs for convicted adult sex offenders to be compared and contrasted in order to address the research questions of interest. A systematic review of the large number of primary research studies that have been conducted on this topic was not warranted because of the recent proliferation of systematic reviews in the SOT field.

By producing an appraisal and summary of seven moderate-to-high quality systematic reviews in one place, this overview provides the opportunity for decision makers to gain a clearer picture of the overall effects of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy on recidivism among the convicted adult male sex offenders. To our knowledge, no other overview using an explicit and systematic method to inform SOT practice has been previously published.

The strengths of this overview of systematic reviews pertain to the comprehensiveness of the literature searches, the criterion-based selection of relevant evidence, the rigorous appraisal of validity, and the evidence-based inferences. The search strategy is very likely to have identified the majority of systematic reviews in this topic. Likewise, the identification of multiple publications is also an important strength of this overview, as it prevented the inclusion of duplicate data that may have skewed the evidence in the analysis of the results. In order to assess the methodological quality of the systematic reviews included in the overview, we adopted a comprehensive strategy that focused mainly on the control of bias that can affect the systematic review process.

Although this overview used a scientifically rigorous approach, it has several limitations. One potential limitation is its restriction to English-language publications. There is, however, no evidence on the impact of the language of publication on the results of overviews of systematic reviews. It is therefore difficult to predict how the exclusion of non-English reviews may have biased the results of this overview. It should also be noted that although only systematic reviews published in English language were included in this overview, some of the included reviews did not set language restrictions in their searches for primary studies.

Restrictions were also applied in terms of publication year (i.e. 1998 onward). The date restriction was applied to ensure that the evidence collected was current and clinically relevant since many changes have occurred during the past two decades in the SOT field in terms of goals, content, methods, style, and other treatment characteristics. However, SOT outcome data prior to 1998 were available, as the primary research studies included in the selected systematic reviews were published/reported as far back as 1953.

The systematic reviews were initially selected by examining the abstracts of these articles, and it is possible that some studies were inappropriately excluded prior to the examination of the full-text article. However, where details were lacking, ambiguous papers were retrieved as full text to minimize this possibility. Only full-text articles were included and the authors of the abstract-only publications were not contacted for full details of their studies. Published reports of systematic reviews that were not accessible through our standard information services were not included.

There are also important limitations in using the overview methodological approach, which synthesizes scientific evidence based only on systematic review-level findings. Not all interventions of interest may be covered by the selected systematic reviews, and relevant primary research might have been overlooked. The evidence provided in such an overview is 'twice removed' from the original primary research aims and findings. Therefore, it is limited in its ability to provide detailed evidence of effectiveness for a certain intervention in a specific population.

Conclusions

This structured overview provides policy planners, practitioners, and other decision-makers in the SOT field with an accessible, good quality synthesis of the best evidence available on the effectiveness of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy delivered within programs for convicted adult male sex offenders.

While the evidence from seven moderate-to-high quality systematic reviews suggests that SOT has the potential to reduce sexual and nonsexual recidivism in this population, the reported findings provide stronger support for the effectiveness of CBT approaches and for programs adhering to the RNR model. However, given the methodological limitations of the available primary research, it was difficult to draw strong conclusions about the effectiveness of SOT programs using various CBT approaches for such a heterogeneous population.

It is still not clear whether all sex offenders require treatment or whether current therapeutic interventions are appropriate for all subgroups of offenders. There also remains much disagreement concerning what are the most useful components and elements of SOT programs that would ensure meaningful rehabilitation for convicted adult male sex offenders and limit the number of future victims. Neither does the available research on SOT outcomes provide clear answers on whether program location matters. More and better designed, conducted, and reported primary and secondary research is warranted to resolve these uncertainties.

Acknowledgements

Production of this document has been made possible by a financial contribution from Alberta Health and Wellness.

We are most grateful to Ms. Maria Ospina who performed independent study selection and quality assessment for the initial structured overview and its update. Ms. Maria Ospina also provided feedback on the draft manuscripts.

We are also most grateful to Dr. R. Karl Hanson, Dr. David Moher, Ms. Susan Connelly, and Dr. William Friend for reviewing and providing information and comments on the draft report of the original structured overview.

The content of this paper represents the views of the authors.

Sources of funding

Alberta Health and Wellness

Conflict of interest

The authors of this article declare no competing interest.

References- Aos, S., Miller, M., & Drake, E. (2006). Evidence-based adult corrections programs: What works and what does not? Olympia, Washington State Institute for Public Policy.

- Bijleveld, C. (2007). Sex Offenders and Sex Offending. Crime & Justice: A Review of Research, 35, 319-387.

- Bilby, C., Brooks-Gordon, B., & Wells, H. (2006). A systematic review of psychological interventions for sexual offenders II: Quasi-experimental and qualitative data. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17, 467-484.

- Brennan, S., & Taylor-Butts, A. (2008). Sexual assault in Canada 2004 and 2007 Ottawa, ON: Minister of Industry.

- Briken, P. (2007). Pharmacological treatments for paraphilic patients and sexual offenders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 20, 609-613.

- Brooks-Gordon, B., Bilby, C., & Wells, H. (2006). A systematic review of psychological interventions for sexual offenders I: Randomised control trials. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 17, 442-466.

- Center for Sex Offender Management (2006). Understanding treatment for adults and juveniles who have committed sex offenses. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs. http://www.csom.org/pubs/treatment_brief.pdf.

- Center for Sex Offender Management (2008). Fact sheet: what you need to know about sex offenders. http://www.csom.org/pubs/needtoknow_fs/pdf.

- Cook, D.J., Sackett, D.L., & Spitzer, W.O. (1995). Methodologic guidelines for systematic reviews of randomized control trials in health care from the Potsdam Consultation on Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 48, 167-171.

- Corabian, P., Ospina, M., & Harstall, C. (2010). Treatment of Convicted Adult Male Sex Offenders. Edmonton AB: Institute of Health Economics.

- Grubin, D. (2007). Second expert paper: sex offender research Liverpool, UK: Forensic Mental Health.

- Hanson, R.K., Bourgon, G., Helmus, L., & Hodgson, S. (2009). A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders : risk, need, and responsivity. Ottawa: Public Safety Canada.

- Hanson, R.K., Gordon, A., Harris, A.J., Marques, J.K., Murphy, W., Quinsey, V.L. et al. (2002). First report of the collaborative outcome data project on the effectiveness of psychological treatment for sex offenders. Sexual Abuse: Journal of Research & Treatment, 14, 169-194.

- Hanson, R.K., Bourgon, G., Helmus, L., & Hodgson, S. (2009). The principles of effective correctional treatment also apply to sexual offenders: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36, 891.

- Harris, A., Phenix, A., Hanson, R.K., & Thornton, D. (2003). Static-99 coding rules: Revised 2003 Ottawa, ON: Solicitor General Canada.

- Losel, F., & Schmucker, M. (2005). The effectiveness of treatment for sexual offenders: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 1, 117-146.

- Marshall, W.L., & Marshall, L.E. (2010). Can treatment be effective with sexual offenders or dies it do harm? A response to Hanson (2010) and Rice (2010). Sexual Offender Treatment, 5.

- McGrath, R.J., Cumming, G.F., Burchard, B.L., Zeoli, S., & Ellerby, L. (2010). Current practices and emerging trends in sexual abuse management: The Safer Society 2009 North American Survey. http://www.safersociety.org/professionals.

- Polizzi, D.M., MacKenzie, D.L., & Hickman, L.J. (1999). What works in adult sex offender treatment? A review of prison- and non-prison-based treatment programs. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 43, 357-374.

- Prentky, R., & Schwartz, B. (2006). Treatment of adult sex offenders. http://www.vawnet.org/Assoc-Files_VAWnet/AR_SexOffendTreatment.pdf.

- Schmucker, M., & Losel, F. (2008). Does sexual offender treatment work? A systematic review of outcome evaluations. Psicothema, 20, 10-19.

- Shea, B., Grimshaw, J.M., Wells, G.A., Boers, M., Andersson, N., Hamel, C. et al. (2007). Development of AMSTAR: a measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 7 [10], 7-10.

- Shea, B.J., Hamel, C., Wells, G.A., Bouter, L.M., Kristjansson, E., Grimshaw, J. et al. (2010). AMSTAR is a reliable and v alid measurement tool to assess the methodological quality of systematic reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 62, 1013-20.

- White, P., Bradley, C., Ferriter, M., & Hatzipetrou, L. (2000). Managements for people with disorders of sexual preference and for convicted sexual offenders. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 000251.

Author address

Paula Corabian

Institute of Health Economics

1200 10405-Jasper Avenue

Edmonton, AB, T5J 3N4, Canada

pcorabian@ihe.ca pcorabian@ihe.ca

|